The COVID-19 crisis triggered an unprecedented surge in sovereign debt levels across the globe, posing new questions about the implications for monetary policy. Advanced economies witnessed their debt levels climb from 104% to 113% of GDP between 2019 and 2022, with emerging markets also experiencing a significant increase from 55% to 65% of GDP over the same period. For emerging market economies, this came on the heels of increased borrowing following the global financial crisis, which had already brought debt to record levels. With the IMF projecting these levels to remain high, alongside substantial pressures on public spending and rising interest burdens, a compelling question arises: Could these soaring government debt levels complicate monetary policy at a moment of persistent inflationary pressures?

Central banks might hesitate to raise interest rates to achieve their inflation objectives due to concerns about debt sustainability. Inflation expectations could de-anchor if people believe central banks will inflate away part of the debt or resort to outright monetisation of future deficits. We empirically investigate the relationship between debt and inflation expectations in a recently published working paper (Brandao-Marques et al. 2023).

Identifying government debt shocks

The empirical question we explore is whether rising debt raises inflation expectations. To mitigate identification problems, we use forecast errors from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (WEO) publications to identify unanticipated surprises in government debt. Surprises may capture changes in debt that do not necessarily move one-for-one with the budget deficit and are less likely to be driven by changes in government expenditures, such as the materialisation of hidden contingent liabilities. We focus on long-term inflation expectations (i.e. five-year ahead expectations), which are less likely to be affected by short-term aggregate demand effects. To further reduce the influence of aggregate demand effects and simultaneity, we also condition our estimations on existing debt levels; if debt surprises affect long-term inflation expectations more the higher pre-existing debt levels are, this is unlikely to stem from such demand effects or other shocks.

The impact of government debt shocks on inflation expectations

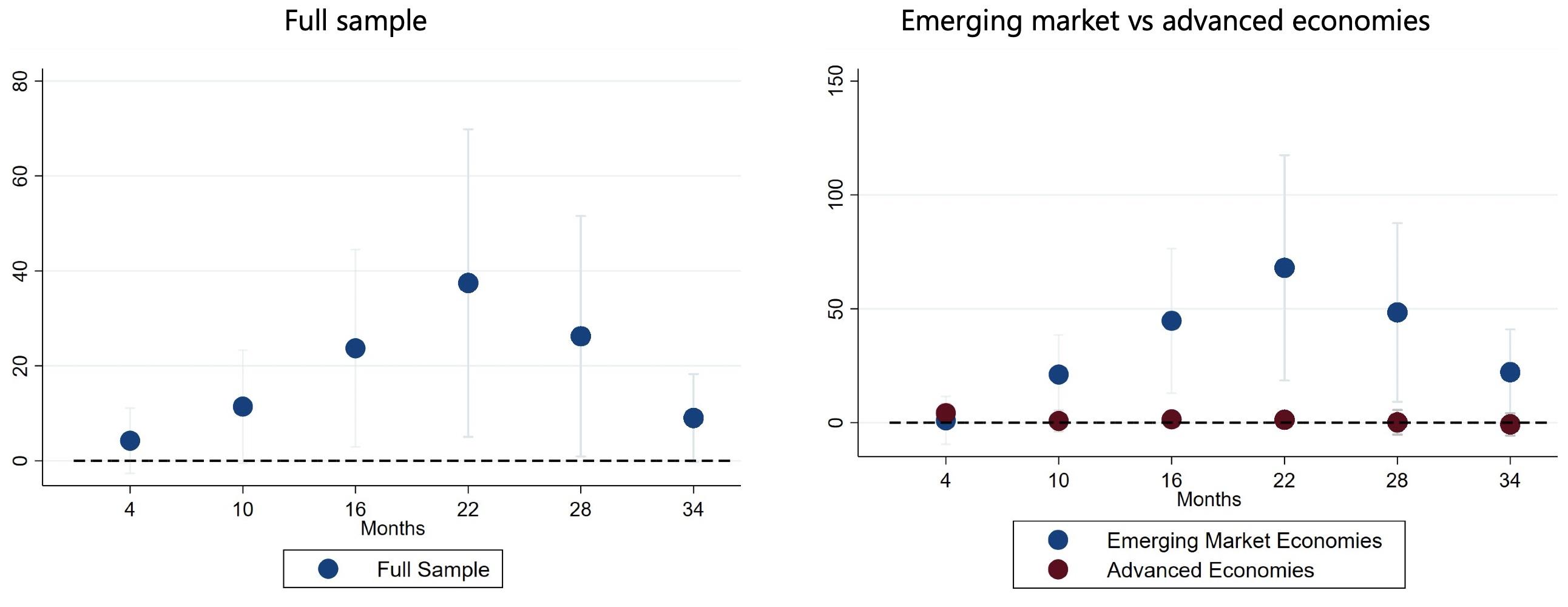

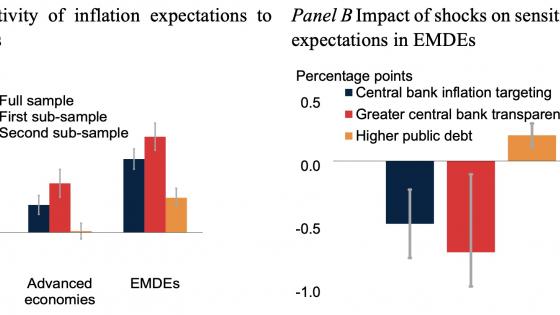

Our sample comprises 48 emerging and low-income economies and 34 advanced economies. Using panel regressions and the local projections method of Jordà (2005), our results suggest that a surprise 10% increase in government debt to GDP leads to a significant increase in long-term inflation expectations after about two years. However, this finding seems to be driven mainly by emerging market economies. For advanced economies, the response of inflation expectations to a debt shock is zero across all horizons. For emerging market economies, however, an unanticipated increase in government debt-to-GDP is associated with a rise in long-term inflation expectations. Specifically, a 10% unanticipated increase in the government-debt-to-GDP ratio results in a statistically significant 20 basis point hike in long-term inflation expectations within the first year after the shock, and reaching a peak of 70 basis points within the second year. The heightened sensitivity of inflation expectations to the fiscal stance could suggest that, on average, economic agents in emerging markets are more sensitive to issues of fiscal dominance – in which the fiscal authority’s solvency constraint determines inflation – than in advanced economies. The result may also capture broader concerns that emerging market central bank independence is less secure than in advanced economies, given weaker institutional frameworks and protections (Unsal and others 2022, Vorisek et al. 2022).

Figure 1 Response of five-year inflation expectations to government debt shocks (basis points, annual rate)

Notes: t=0 is the quarter of the shock. The figures plot for the relevant horizon the five-year ahead inflation expectations response to a 10 percent surprise in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The blue dots denote the inflation expectations response for emerging market economies in our sample while the red dots denote the corresponding response for advanced economies. The whiskers represent 90% confidence intervals. The chart on the left shows the response for the full sample.

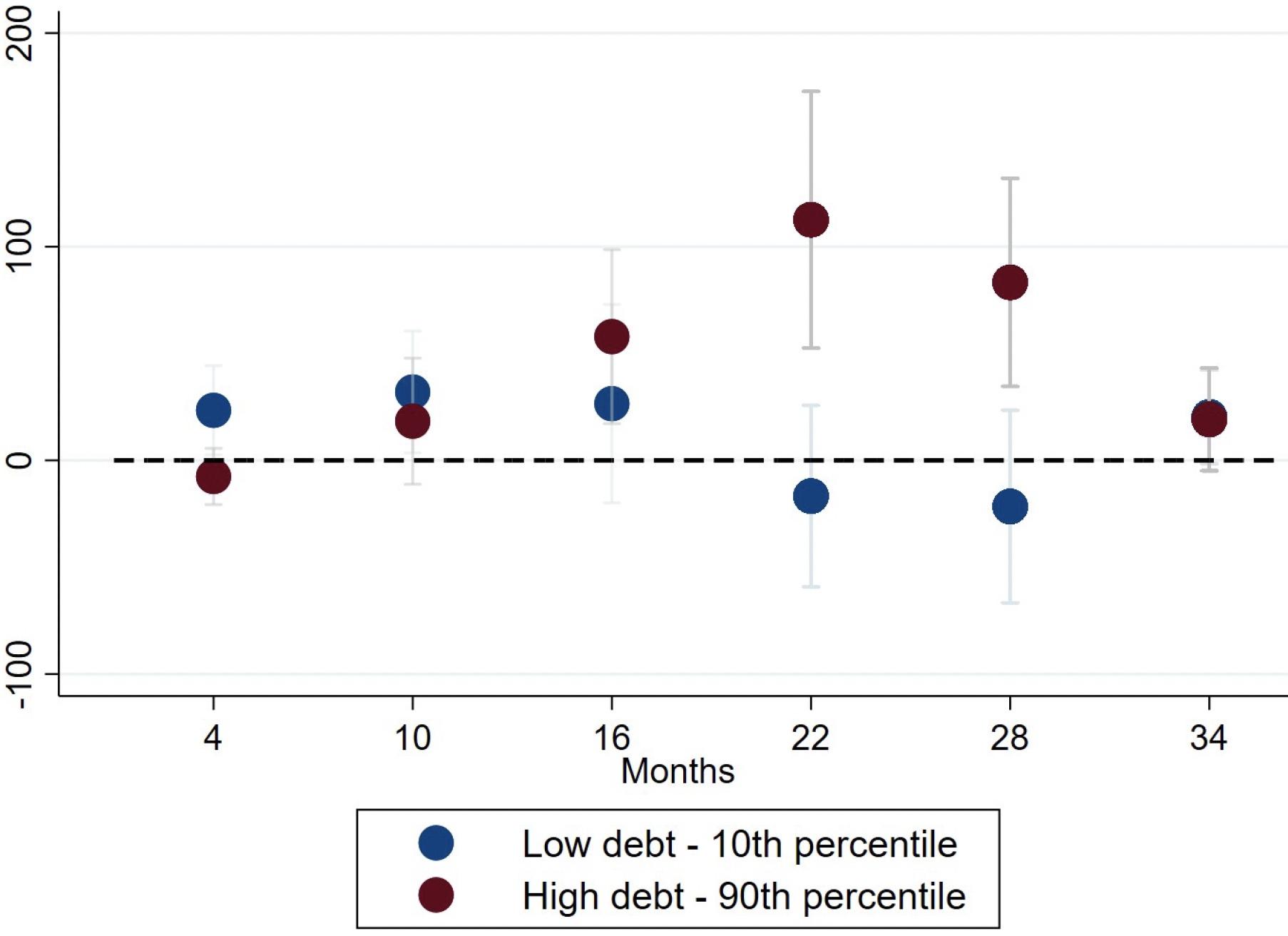

The sensitivity of inflation expectations to debt surprises depends on the debt level, suggesting that the change in inflation expectations is driven by debt concerns. Figure 2 illustrates the state dependence by tracing out the response of inflation expectations for economies with government debt-to-GDP levels at the 10th and 90th percentiles of the emerging market economies. For countries in the low debt group, the impact of the unanticipated debt increase on inflation expectations is statistically insignificant. By contrast, high-debt countries experience as much as a 100-basis point increase in long-term inflation expectations after two years in response to a 10% surprise rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 2 Emerging market economies’ response of five-year inflation expectations to government debt shocks, by initial debt level (basis points, annual rate)

Notes: t=0 is the year of the shock. The figure plots the inflation expectations response to a 10% surprise in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The blue dots denote the inflation expectations response for economies with a debt level at the 10th percentile of the relevant country group sample, while the red dots denote the corresponding response for economies with a debt level at the 90th percentile of the relevant country group sample. The whiskers represent 90% confidence intervals.

Interestingly, the effects are more pronounced with high shares of foreign-currency debt. We find a positive and statistically significant effect of the interaction between foreign currency debt levels, debt levels, and debt surprises. Our results suggest that concerns that a large foreign currency debt share increases a sovereign’s vulnerability to external shocks outweigh the mitigating effects from the central bank’s inability to monetise the share of debt that is denominated in foreign currency. Moreover, in case of a debt crisis, the presence of foreign currency-denominated debt requires a higher level of inflation to reduce the real value of total debt.

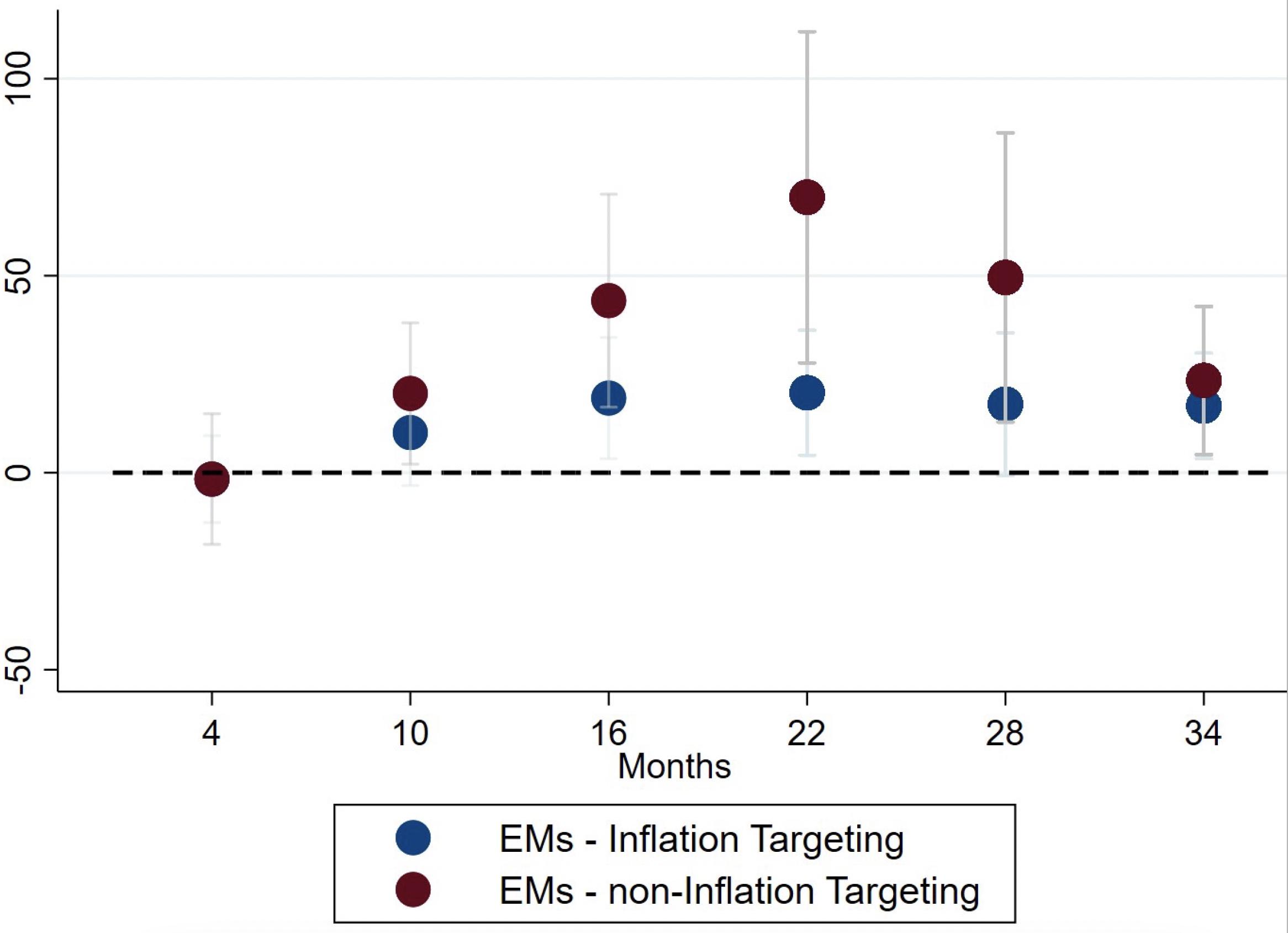

What roles do monetary policy frameworks and credibility play? Economies with central banks that do not formally pursue inflation targeting (IT) display a relatively higher sensitivity of long-term inflation expectations to a debt surprise, but the difference vis-à-vis IT economies is not significant. Nevertheless, the profile of the impulse response for non-IT emerging market economies matches the delayed onset of de-anchored expectations shown in the baseline results for emerging market economies. These results suggest that inflation-targeting emerging market central banks are better able to anchor medium-term expectations in response to fiscal shocks than their non-IT counterparts.

Figure 3 Emerging market economies’ response of inflation expectations to government debt shocks, by inflation targeting regime classification (basis points, annual rate)

Notes: t=0 is the year of the shock. The figure plots the response of five-year inflation expectations to a 10% surprise in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The blue dots denote the inflation expectations response for economies with inflation-targeting central banks in the relevant country group sample while the red dots denote the corresponding response for economies with non-inflation targeting central banks. The shaded region represents 90 percent confidence intervals.

Overall, our analysis sheds new light on fiscal-monetary policy interactions, providing novel evidence on the role of debt in shaping inflation expectations (for a different approach, see Grigoli and Sandri 2023). In emerging market economies with high government debt levels, bringing debt to a sustainable path is likely to be important for containing inflation. This is particularly relevant at the current juncture, with record debt levels and inflationary pressures around the world having proven strong and persistent. In the medium term, adopting modern, forward-looking monetary policy frameworks such as inflation targeting can reduce inflationary concerns associated with government debt, creating more space for both monetary and fiscal policy.

References

Brandao-Marques, L, M Casiraghi, G Gelos, O Harrison, and G Kamber (2023), “Is High Debt Constraining Monetary Policy? Evidence from Inflation Expectations,” IMF Working Paper 2023/143.

Grigoli, F and D Sandri (2023), “High public debt levels raise household inflation expectations – but central banks aren’t powerless,” VoxEU.org, 13 April.

Jordà, Ò (2005), “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections”, American Economic Review 95(1): 161-182.

Unsal, D F, C Papageorgiou and H Garbers (2022), “Monetary Policy Frameworks: An Index and New Evidence,” IMF Working Paper WP/22/22.

Vorisek, D, U Panizza, M A Kose, H Matsuoka and J Ha (2022), “Anchoring inflation expectations in emerging and developing economies”, VoxEU.org, 8 February.