While the Oxford Dictionary defines charitable as “helping people who are poor or in need”, there is growing questioning about the likely political objectives behind philanthropy. First, as documented by Reich (2018), the observed pattern of giving – at least in the US – is hard to reconcile with expectations of redistributive outcomes. According to Reich’s estimates, “at most one-third of charity is directed to providing for the needs of the poor” (2018: 87).

Second, Petrova et al. (2020) use micro data from the American Red Cross and the US Federal Election Commission as well as a lab experiment to show that individuals substitute between political contributions and charitable donations. Corporate philanthropy is also used as a tool for political influence: according to Bertrand et al. (2020), 16.1% of total US corporate charitable giving can be interpreted as politically motivated (see also Bertrand et al. 2018).

Yet, it is hard to isolate and, even more, to quantify the political motivations behind charitable giving. In the first place, it seems important to distinguish the behaviour of small donors from that of large ones. While there are more small donors – with respect to the number of donors – they may not represent the majority of the donations received by charities (given the smaller average size of their donations). The relatively small size of small donors’ contributions does not necessarily point to a lack of political motivation. As Bouton et al. (2022) document, the share of small donors’ contributions in US politics is growing, even though none of those donors may be pivotal. But small donors are less likely to buy political influence with their donations.

On the other hand, large donations to charities might both be driven by political considerations and be seen as a political investment. While we tend to think of wealthy donors when questioning the political objectives of philanthropy, they have been mostly overlooked in the existing literature. In a recent paper (Cagé and Guillot 2022), we fill this gap by studying the motivations behind wealthy donors. To do so, we exploit an exogenous shock on the price of charitable giving for those donors.

The 2017 wealth-tax reform in France

In France, both charitable and political donations benefit from a 66% (nonrefundable) income tax credit, but only charitable donations are eligible for a 75% wealth-tax credit. We exploit the 2017 wealth-tax reform in France that transformed the solidarity tax on wealth in real-estate tax. This reform did not modify the tax schedule but restricted the definition of the tax base to real-estate assets, excluding other assets (in particular financial assets) that were previously included. With this wealth-tax reform, two-thirds of the households liable to the wealth tax on their 2016 wealth are no longer liable for their 2017 wealth, and thus can no longer benefit from the 75% wealth-tax deductions for charitable giving.

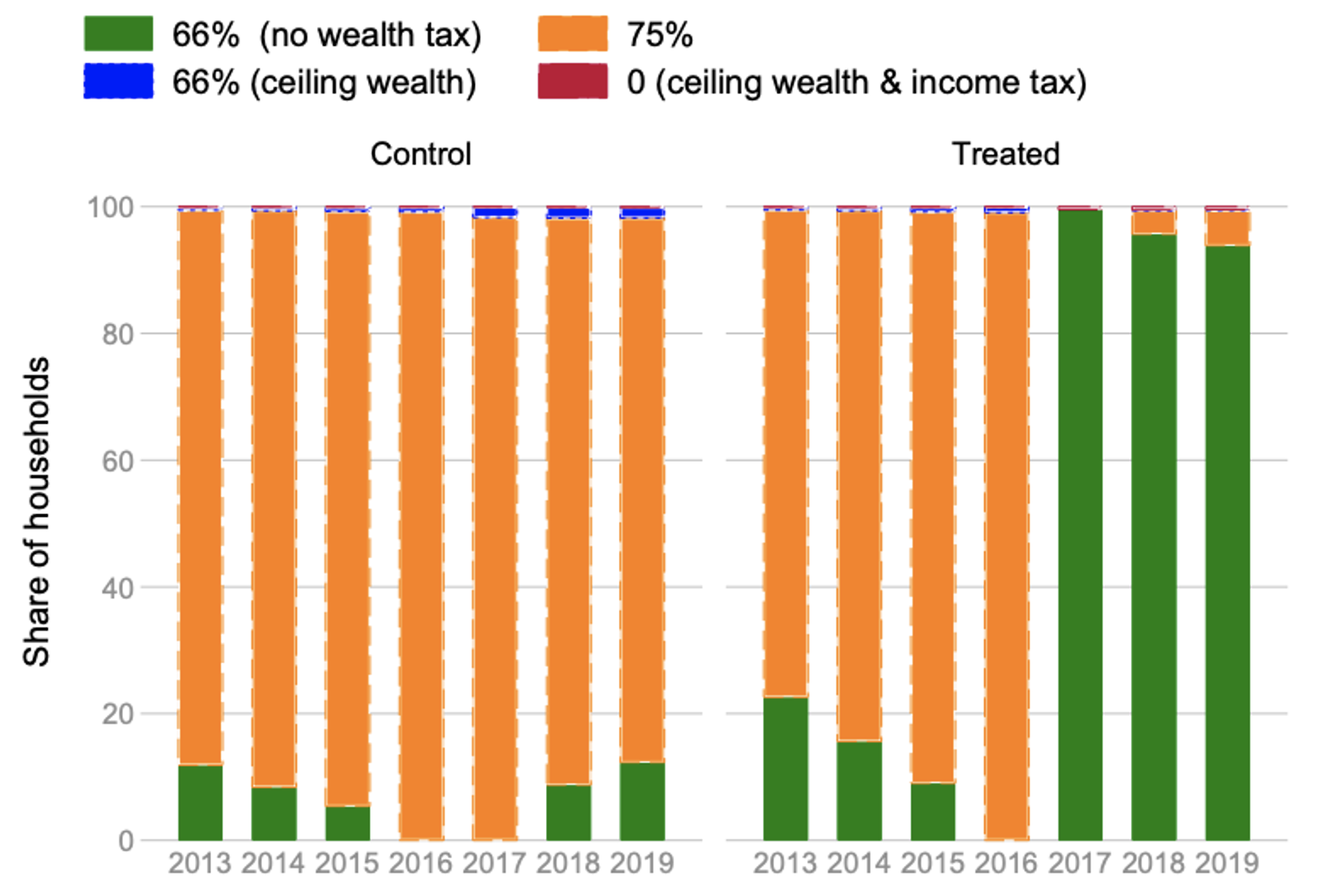

In other words, the reform created a shock on the price of charitable giving – that price increases from 25% to 34% of the amount of the gift, given that the income tax credit is ‘only’ equal to 66% of the donations – but not on the price of political donations, as political giving was not eligible for the wealth-tax deduction before the reform. This is illustrated in Figure 1, where we plot the underlying variations in the price of charitable giving. While the 115,013 ‘control’ households who continue paying the real-estate tax after the reform still benefit from a 75% tax credit, the price of charitable giving increases from 25% to 34% for the 236,216 ‘treated’ households in 2017.

Figure 1 Evolution of the marginal price of charitable giving following the 2017 wealth-tax reform

Notes: The figure plots the change in the marginal price of charitable giving for the 115,013 ‘control’ households who continue paying the real-estate tax following the 2017 wealth-tax reform (on the left) and the 236, 216 ‘treated’ households (on the right) who are no longer eligible for the wealth tax in 2017. Green bars show the share of the households not eligible for the wealth tax and can thus only benefit from the 66% income-tax credit. Orange bars show the share of the households eligible for the wealth tax and can thus benefit from the 75% wealth-tax credit. Blue bars show the share of the households eligible for the wealth tax but who face the €50,000 wealth-tax credit cap. Finally, red bars show the share of the households eligible for the wealth tax but who face both the €50,000 wealth-tax credit cap and the income-tax ceiling. Source: Cagé and Guillot (2022).

Note that these tax units represent 1% of the households but 4.8% of the total gross income, 16% of the charitable donations declared in the income tax returns, and 13.8% of the declared political donations. Furthermore, they represent 22.5% of the total (non-political) income and wealth-tax donations in France.

Less taxes… but less charitable donations…

From the outside, one might expect the repeal of the wealth tax to increase the total amount of charitable giving. The wealth-tax reform indeed represented a wealth-tax gain for a number of households, i.e. a positive income effect. On average, we observe a €10,820 decrease in tax paid by the households who continue paying the real-estate tax after the reform (but no longer pay taxes on their financial assets) and a €7,702 decrease for the households who completely leave the wealth tax. This positive income shock could have a positive effect on charitable donations through a resource effect: with more cash at their disposal, households could decide to contribute more (Bakija and Heim 2011).

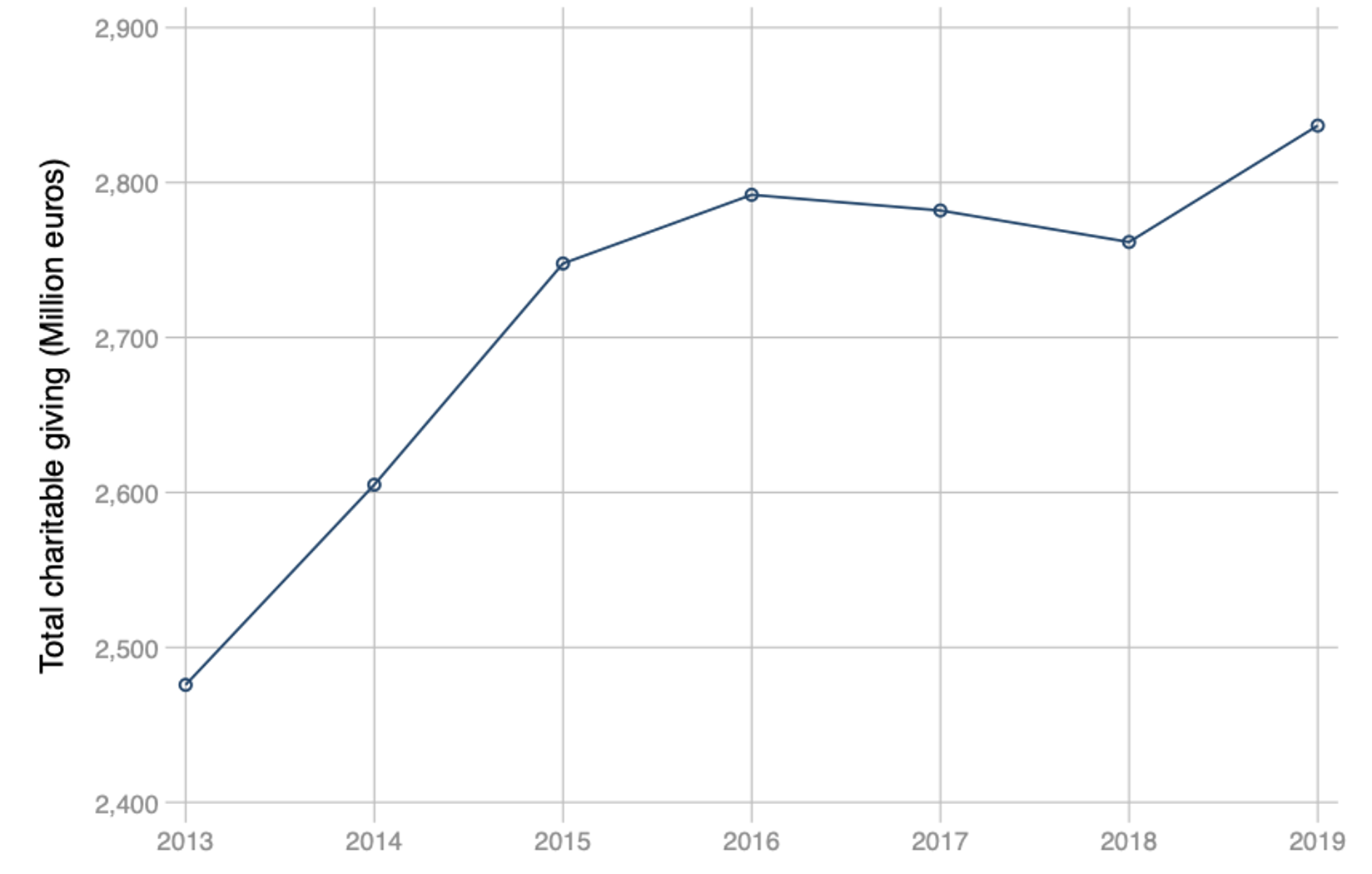

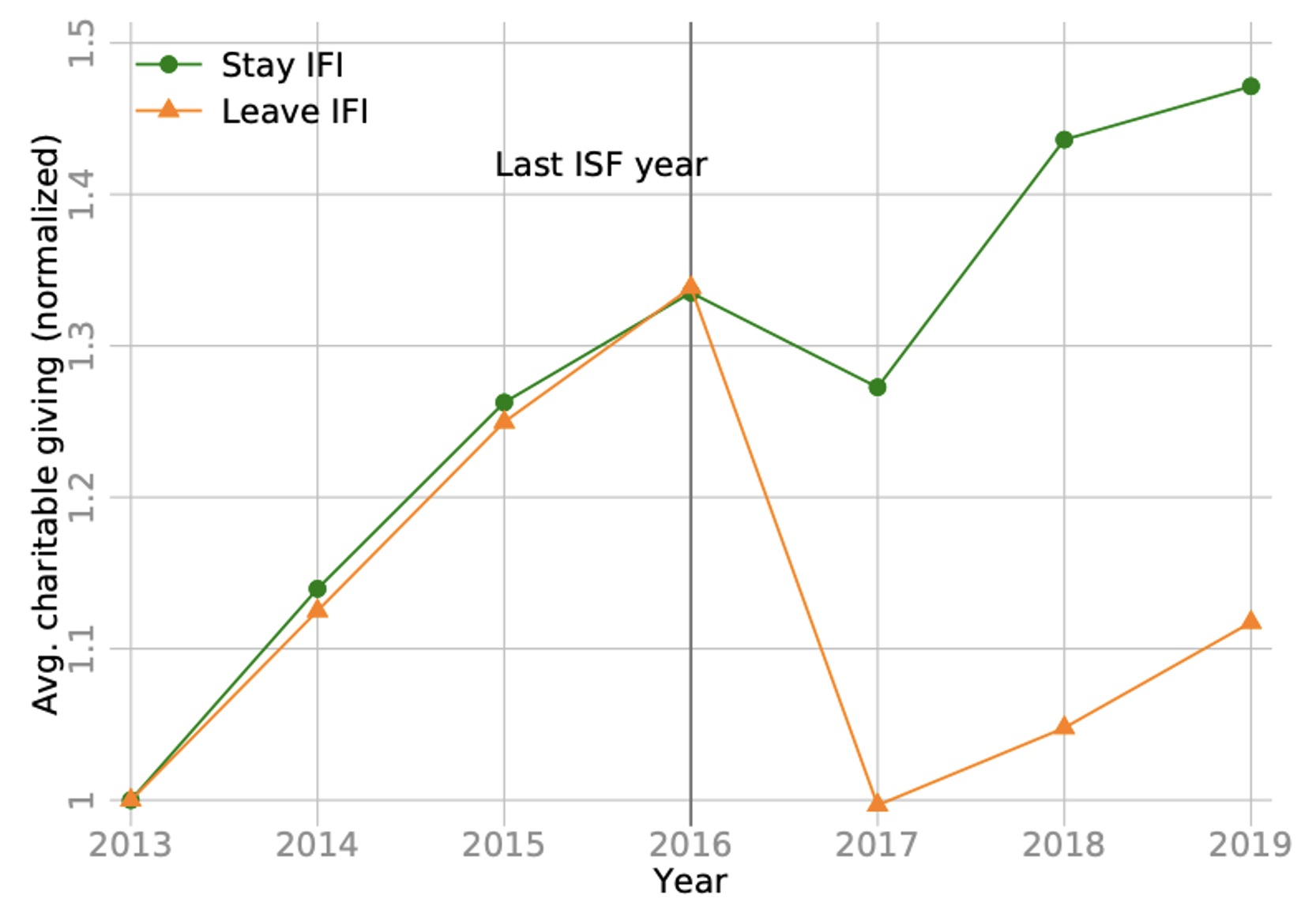

Yet, we observe the contrary. First, as illustrated in Figure 2, we document a decline in overall donations (declared either to the wealth or to the income tax) to charities between 2016 and 2017–18. Then, Figure 3 shows the separate evolution of the average amount of charitable donations for the control households who continue paying the real-estate tax following the wealth-tax reform (‘stay IFI’) – and thus continue to benefit from the 75% wealth-tax deduction – and the treated households who are no longer liable to the wealth tax in 2017 (‘leave IFI’) – or, therefore, to the 75% deduction. While the amount given by these two groups were similar until 2016, the reform led to a striking drop in the amount given by the treated households compared to the control group.

Figure 2 Evolution of the total amount of charitable donations, 2013–2019

Figure 3 Impact of the wealth-tax reform on charitable giving

Notes: The figure plots the average amount of charitable donations (normalised to one in 2013) for the ‘control’ households (‘stay IFI’ – green line with dots) who continue paying the real-estate tax following the 2017 wealth-tax reform and the ‘treated’ households (‘leave IFI’ – orange line with triangles) who are no longer liable to the wealth tax in 2017. Our sample includes all households subject to the wealth tax in 2016 who face wealth-tax gain between €0 and €15,000 following the reform. Charitable giving includes all charitable donations declared on both the income tax and the wealth-tax returns. Source: Cagé and Guillot (2022).

How can we explain such a drop that came despite the positive resource effect? The fact is that the wealth-tax reform increased the price of charitable giving. Before the reform, for the wealth-tax payers, the marginal price of a €100 charitable donations was only €25 (the donor benefited from a €75 tax rebate), but after the reform it increased to €34. Consistent with the existing literature measuring the tax-price elasticity of giving (Feldstein and Taylor 1976, Meer and Priday 2020, Fack and Landais 2010), this price increase led to a decrease in the amount contributed.

…and more political ones

The goal of our research is to study whether, at the top of the wealth distribution, political and charitable donations are substitutes or complements. We thus investigate whether the decline in the amount of donations to charities affected the donations to the political parties. Note here that we aim to capture the impact of a change in charitable donations driven by exogenous variations – i.e. a change that does not directly impact political donations. This is the case for households facing similar wealth-tax gains following the 2017 wealth-tax reform: the reform was a negative shock on the price of charitable donations but not on the price of political ones, as political donations are not eligible for the 75% wealth-tax credit.

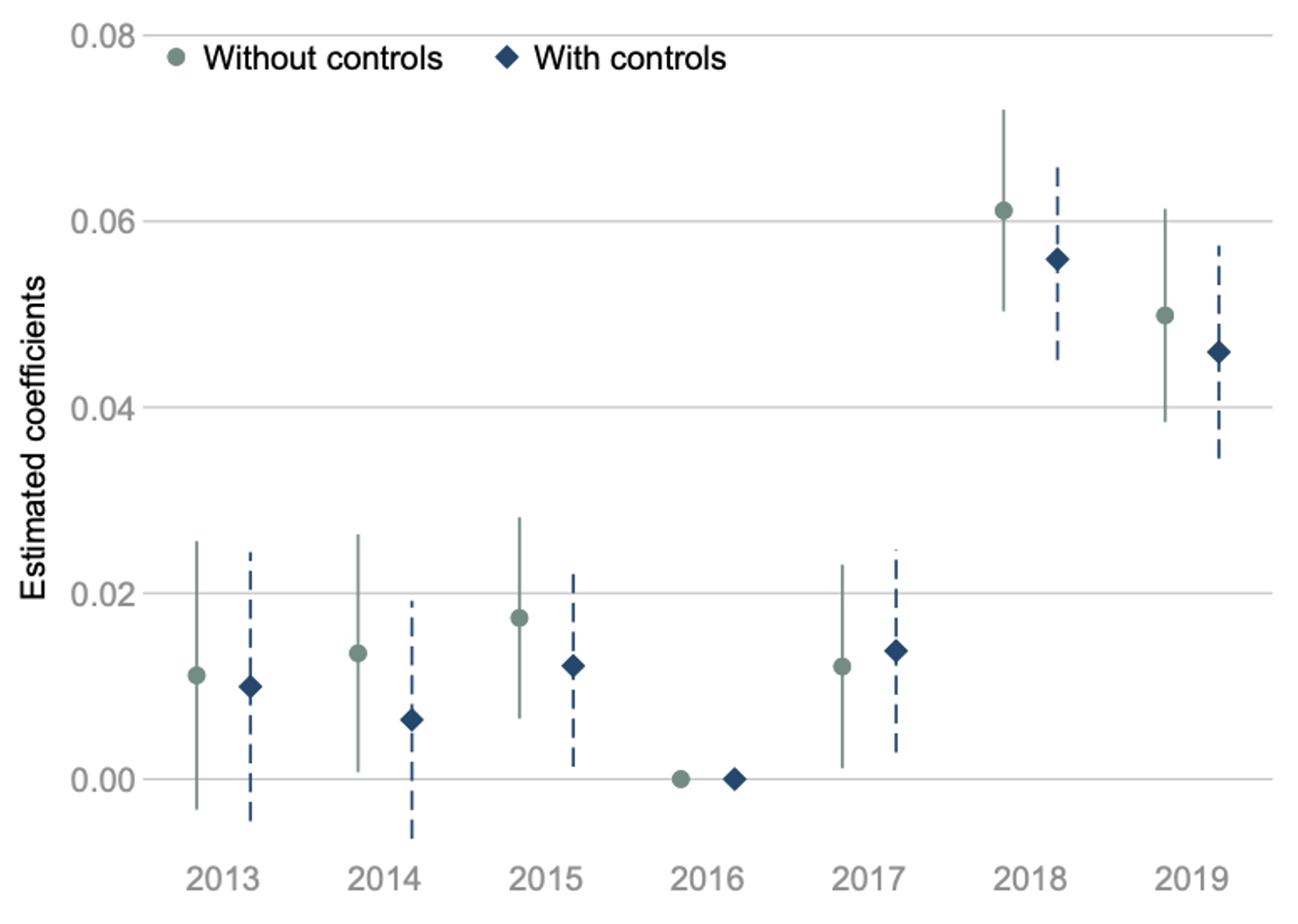

Figure 4 reports the estimated change in political donations for the households in the treatment group (i.e. the households who leave the wealth tax) relative to the ones in the control group (the households who continue paying the real-estate tax). Clearly, the treatment status has no impact on the political-giving behaviour before the wealth-tax reform, while we observe a jump after 2017 in the amount contributed by the treated households compared to the control ones.

Figure 4 The impact of the 2017 wealth-tax reform on political donations

We then turn to the causal impact of a change in charitable donations on political ones. To do so, we take advantage of the fact that the wealth-tax reform was an exogenous shock on the price of charitable donations but not on the price of political contributions. We find that a 1% increase in the price of charitable giving leads to a 0.12% increase in political donations. In other words, political and charitable donations seem to be substitutes.

In terms of magnitude, our estimates imply that a 36% increase in the tax price of charitable giving (from 25% to 34%) is associated with a 4.32% increase in political donations. Given that we show that a 1% increase in the price of charitable giving leads to a 0.90% decrease in charitable donations, our findings imply that the 36% increase in the tax price of charitable giving leads to a 32.4% decrease in charitable donations. Hence, at average charitable giving (€1,087.1) and political donations (€22), a €352.2 decrease in charitable giving is associated with a €1 increase in political donations. Between 2016 and 2017, wealth-tax charitable donations decreased by €267.0 million; according to our estimates, this can be associated with a €758,117 increase in political donations, which corresponds to 11.6% of the total political donations made by wealth-tax donors in 2017.

Pro-business parties benefited the most from the rise in political donations

Who benefited the most from the rise in political donations? To answer this question, we combined information on commune-level donations received by each political party and treatment intensity by commune. The intensity of the treatment is equal to the share of the households eligible for the wealth tax in 2016 but not in 2017, normalised by the total number of households eligible for the wealth tax in 2016. In our preferred specification, the ‘treated communes’ are those whose treatment intensity is equal to 100.

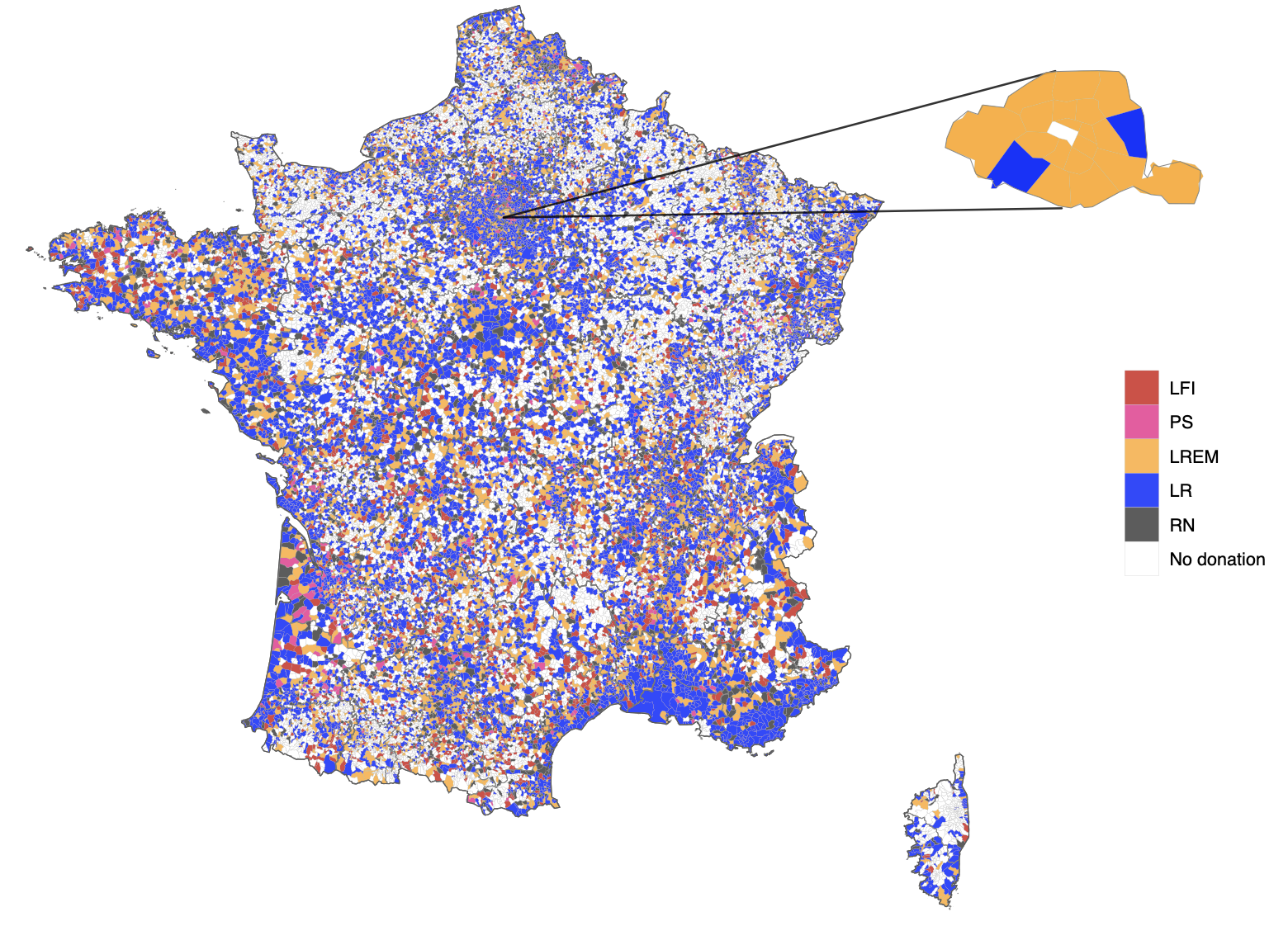

We collect information on commune-level political donations to the five main political parties that presented a candidate in the 2017 French presidential elections: La France Insoumise, the Parti socialiste (Socialist Party), La République en Marche, Les Républicains, and the Rassemblement National. Figure 5 illustrates their geographical allocation, by showing the distribution of the party which receives the highest donation at the commune level during the 2016–2020 period.

Figure 5 Party receiving the highest amount of donation, 2016–2020

Notes: The map shows the party receiving the highest political donation (using the 2016–2020 average) in each commune, with the following colour code: La France Insoumise (LFI) is in red, the Parti socialiste (PS) is in pink, La République en Marche (LREM) is in orange, Les Républicains (LR) is in blue, and the Rassemblement National (RN) is in red. The commune is white if no donations are observed during the period. The political donations data come from the political party accounts. Here is the map in vector format. Source: Cagé and Guillot (2022).

First, we find that, consistent with our other results, there is a 1.3% to 1.5% increase in the total overall political donations (normalised by the number of tax households) made in the treated communes compared to the control communes following the wealth-tax reform. Second, we show that this increase in donations did not benefit all political parties in a similar way. The tax reform mostly benefited the right-wing/pro-business Les Républicains party, whose donations in treated communes increased by 2.3% to 2.5% following the reform compared to the control ones (an increase that is not due to a rise in the political support for this party since 2017). If anything, we observe a small decrease in the donations received by the left-wing movements, particularly strong for the Socialist Party.

How can we explain this heterogeneity in the amount received by the different parties? We need to investigate what the donations to political parties substituted for – and ultimately explore whether there is also heterogeneity on the charitable-giving side. We therefore classify nonprofit organisations recognised as ‘being of public utility’ – and that can benefit from the wealth-tax credit – into politically-involved and non-politically-involved foundations, using their stated purposes. Examples of the former include politically-involved think-tanks such as the Fondation Jean Jaurès on the left and the Fondation pour la recherche sur les administrations et les politiques publiques (iFRAP) on the right. An example of a non-politically-involved foundation is ATD Quart Monde, which works to eradicate chronic poverty.

Relying on these foundations’ financial accounts, we document a decline in the donations received by the political FRUPs compared to the non-political ones following the wealth-tax reform. Anecdotally, the example of the pro-business iFRAP is striking. While donations received by this organisation slightly increased between 2013 and 2016, they began to decline from 2017 – a trend that accelerated since 2020. Obviously, we cannot determine whether some former iFRAP contributors decided to substitute their charitable donation with a political donation made directly to Les Républicains party (that benefited – as documented above – from the relative rise in political donations). But our anecdotal evidence on both parties and foundations points toward this direction.

Policy implications: Capping charitable giving?

Why do people make charitable donations? As appears clearly from our study, political reasons play a significant role. This might not be the case for all donors, but it certainly is at the top of the wealth distribution: among households eligible for the wealth tax in 2016, we document that a 1% increase in the price of charitable giving leads to a 0.12% increase in political donations, and that this effect is particularly strong at the top of the income distribution. These results are of particular importance given that, until now, due to the use of survey data to study donors’ motivations, large donors have mostly been overlooked in the literature.

These findings question the relevance of the existing tax incentives for giving. First, these incentives were introduced with the justification that charitable organisations may provide valuable social services. But our findings pointing to political motivations behind charitable giving challenge such a choice, at least for wealthy donors. Further, one wonders whether the foundations that can benefit from such tax deductions should be more precisely defined, at least in countries where there are no tax deductions for political donations. Our findings also question the relevance of having tax policies for charitable giving that are much more generous than for political donations.

Finally, while in many Western democracies campaign finance laws place limits on political donations (see e.g. Cagé 2018, 2020), to the extent of our knowledge, no country has introduced a cap on charitable giving. Our findings question this absence of regulation. Indeed, for a politically motivated donor who faces a cap on their political donations, giving to a think tank can indeed be an easy alternative.

References

Bakija, J, and B T Heim (2011), “How does charitable giving respond to incentives and income? New estimates from panel data”, National Tax Journal 64(2): 615–50.

Bertrand, M, M Bombardini, R Fisman and F Trebbi (2018), “Tax-exempt lobbying: Corporate philanthropy as a tool for political influence”, VoxEU.org, 3 September.

Bertrand, M, M Bombardini, R Fisman and F Trebbi (2020), “Tax-exempt lobbying: Corporate philanthropy as a tool for political influence”, American Economic Review 110(7): 2065–102.

Bouton, L, J Cagé, E Dewitte and V Pons (2022), “Small campaign donors”, NBER Working Paper 30050.

Cagé, J (2018), Le prix de la démocratie, Fayard (published in English as The price of democracy, Harvard University Press, 2020).

Cagé, J (2018), “The price of a vote”, VoxEU.org, 26 October.

Cagé, J, and M Guillot (2022), “Is charitable giving political? Evidence from wealth and income tax returns”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17597.

Fack, G, and C Landais (2010), “Are tax incentives for charitable giving efficient? Evidence from France”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2(2): 117–41.

Feldstein, M, and A Taylor (1976), “The income tax and charitable contributions”, Econometrica 44(6): 1201–22.

Meer, J, and B A Priday (2020), “Tax prices and charitable giving: Projected changes in donations under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act”, Tax Policy and the Economy 34: 113–38.

Petrova, M, R Perez-Truglia, A Simonov and P Yildirim (2020), “Are political and charitable giving substitutes? Evidence from the US”, NBER Working Paper 26616.

Reich, R (2018), Just giving: Why philanthropy is failing democracy and how it can do better, Princeton University Press.