Collateral plays a central role in how we understand macroeconomic fluctuations, such as the financial cycle. Bernanke and Gertler (1989) famously lay out that changes in asset prices can affect wider economic conditions through a ‘financial accelerator’ mechanism when these assets are used as collateral. Put simply, rising asset prices increase collateral values and allow firms borrowing against this collateral to borrow more. Increased borrowing by firms in turn boosts economic activity and further increases asset prices, thus restarting the cycle by again increasing collateral values. Of course, this mechanism can also work in reverse, with falling asset prices restricting firms’ borrowing capacity and depressing wider economic activity. In practice, this mechanism has played out most prominently via real estate markets during the global financial crisis and in a number of developed economies in the 1990s (see also Hericourt et al. 2022 on implications for productivity during the pre-crisis boom).

In our recent paper (Horan et al. 2023), we examine how the commercial real estate downturn created by the Covid-19 pandemic (Mittal et al. 2022, Henricot et al. 2022) affected firms’ capacity to borrow from banks in the euro area. We use a new credit registry dataset which provides information on all lending to firms by euro area banks. Our study benefits from monthly collateral-level information on almost 5 million pieces of real estate collateral across the euro area, which allows us to study – to our knowledge for the first time – the banking system’s role in driving the financial accelerator mechanism. In particular, this dataset allows us to directly examine banks’ revaluation of collateral during a market downturn and their willingness to lend against this collateral during crisis periods.

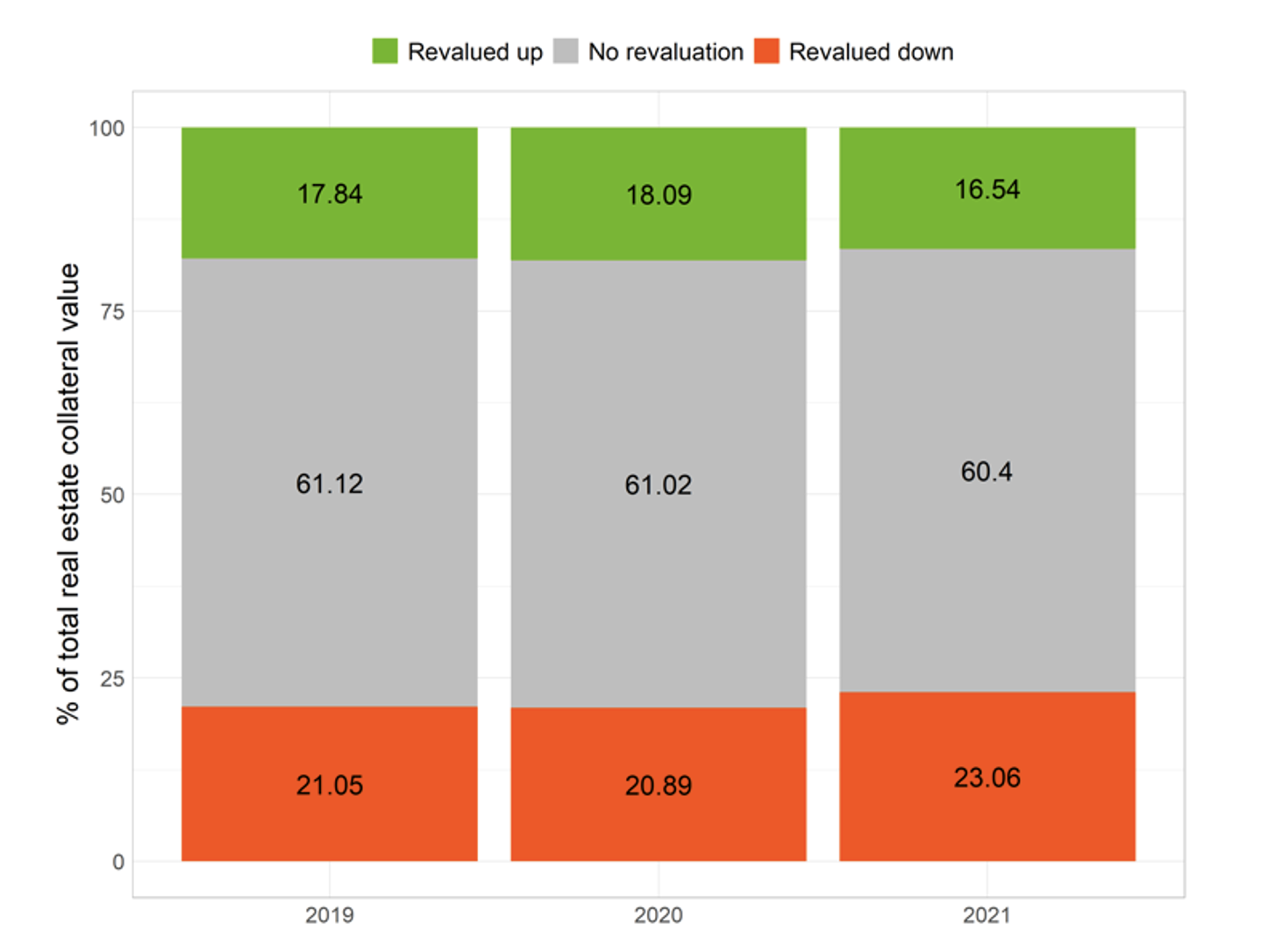

Surprisingly, we find that during the pandemic, banks did not significantly lower the reported valuations of the real estate they held as collateral. This challenges textbook economic theory, which would suggest that banks automatically revise collateral values downwards during a crisis when asset prices fall. In Figure 1, we break down the stock of real estate collateral held by euro area banks by the size of its revaluation over the course of the years 2019, 2020 and 2021. Revaluation of real estate collateral by banks appears to have remained largely unchanged during the pandemic compared to 2019.

Figure 1 Real estate collateral revaluation by euro area banks remained largely unchanged following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic

Note: Revaluations for the year are calculated as a change of value from the beginning of the year or the earliest entry, to the end of the year or the latest entry. Revaluation size is calculated as the proportional change from the initial value for a given collateral item in the year. Data refers to collateral held against loans to non-financial corporations only.

This suggests that the assumptions made about the role of the banking system in a simple version of the financial accelerator model may be somewhat simplistic. Textbook assumptions may ignore certain factors which keep banks from simply mapping changes in market values onto collateral values. For example, revaluations may be costly to carry out or banks may wish to avoid revaluing collateral where a downward revaluation could have implications for factors such as their capital requirements or risk weights.

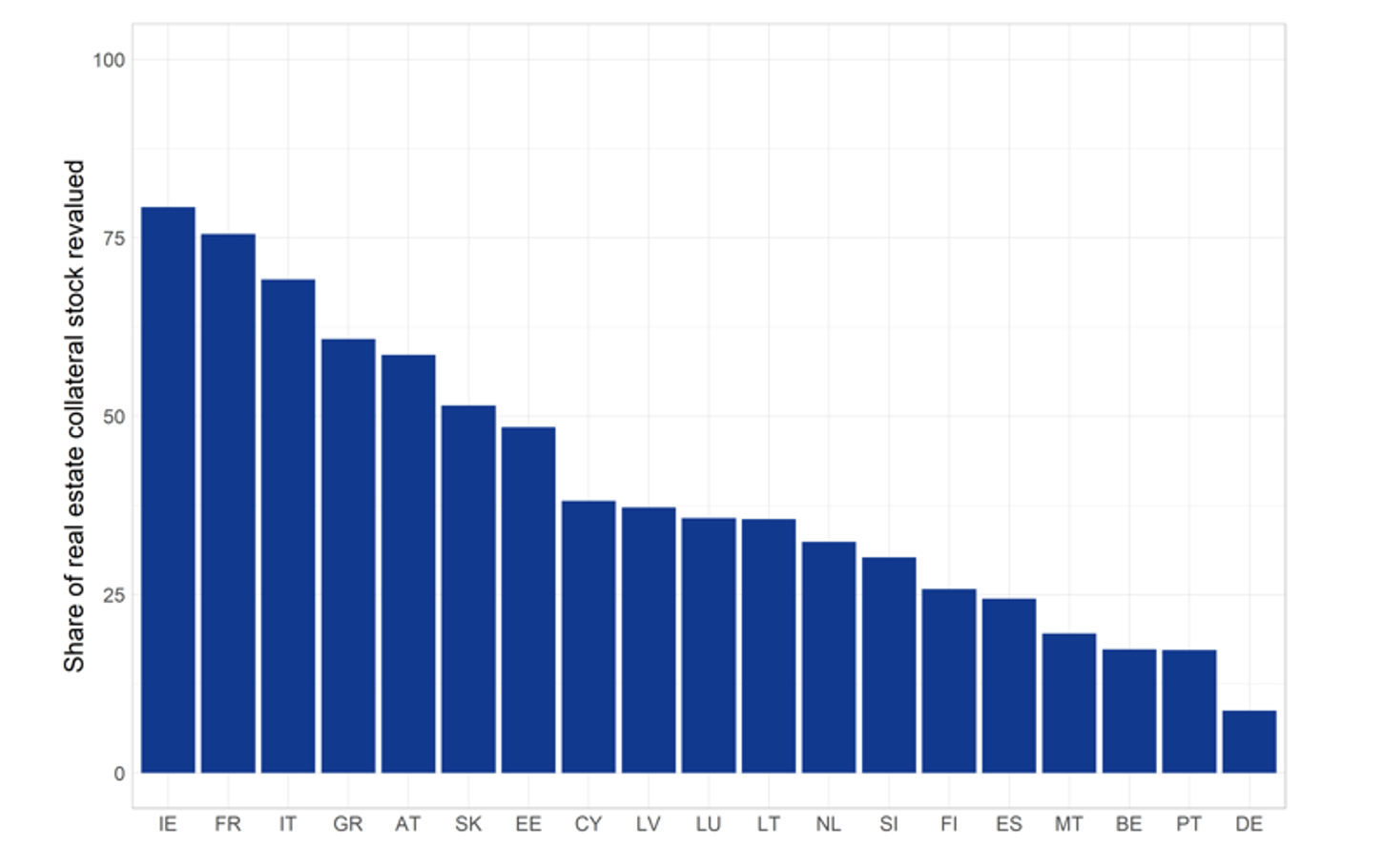

Moreover, the share of collateral revalued each year varies widely across euro area countries, suggesting that factors which disincentivise or incentivise revaluation may be quite different in each country (Figure 2). For example, the approach taken to calculating collateral values could influence revaluation frequency, with valuation techniques aiming to capture long-run values arguably requiring fewer updates than market value approaches. This suggests that the same asset price drop could have markedly different implications for borrowing dynamics in different euro area countries. This finding is particularly important in the current context of monetary tightening. All euro area countries are subject to the same changes in interest rates, but these could have different implications for lending across countries if banks incorporate them into collateral valuations in different ways or at different speeds.

Figure 2 Revaluation behaviour shows clear national trends, with the share of collateral revalued in a given year varying dramatically across countries

Note: The chart shows the share of collateral revalued over the course of 2020. National patterns are almost identical in 2019 and 2021. Data refers to collateral held against loans to non-financial corporations only.

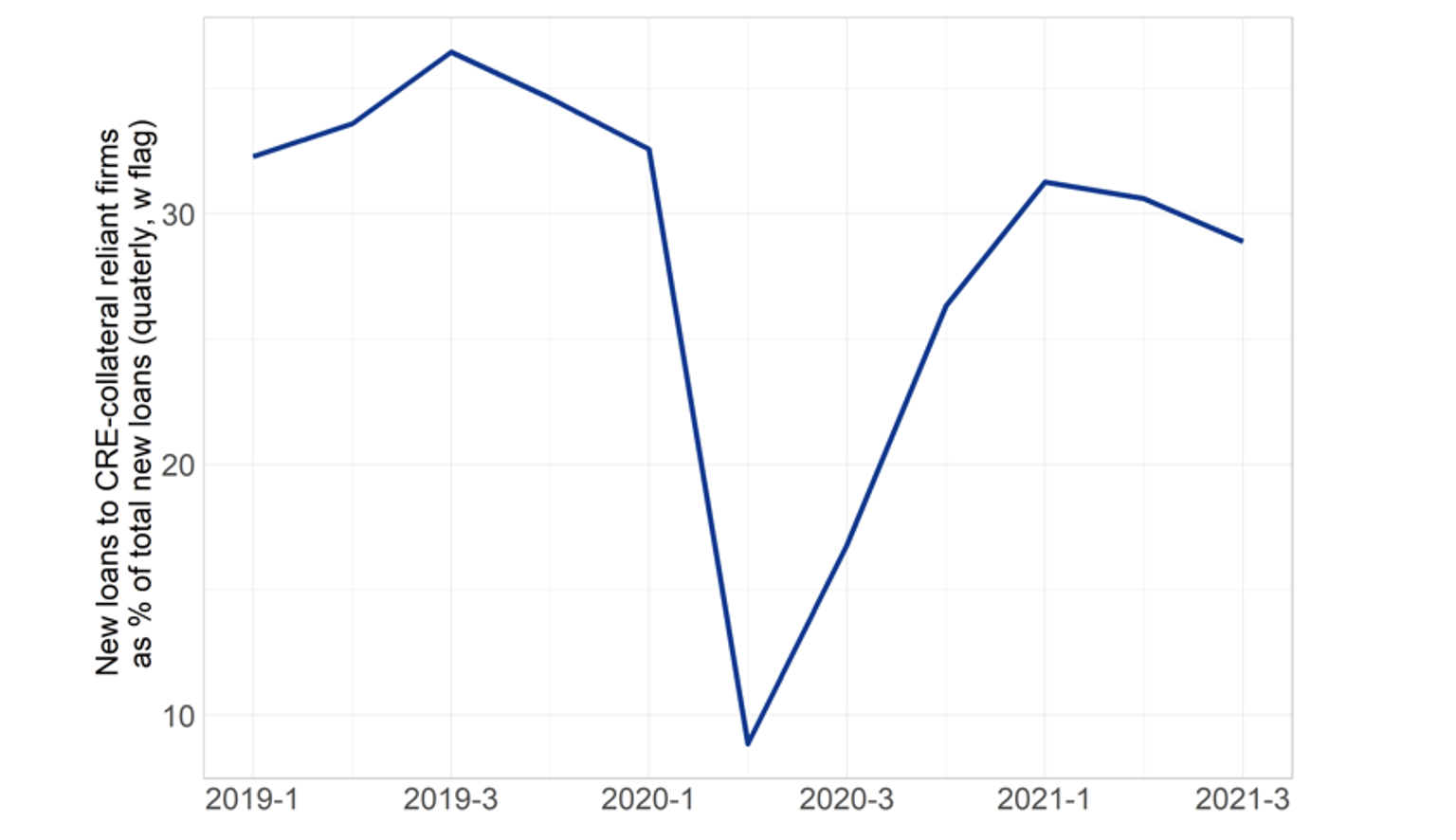

Next, we examine how firms' use of real estate collateral and banks' treatment of it affected lending outcomes during the crisis. As we don’t see a widespread downward revaluation of collateral following the outbreak of the crisis, first we simply examine how firms' use of the real estate as collateral in general affected their capacity to borrow. We find that lending relationships which had relied on real estate collateral prior to the pandemic received significantly less credit following the outbreak of the pandemic. The share of loans to firms reliaton on real estate collateral dropped sharply from over 30% of quarterly new loans to less than 10% with the outbreak of the pandemic (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic the share of new lending to firms reliant on real estate collateral dropped sharply

Note: Bank-firm relationships are categorised based on their real estate collateral reliance pre-Covid-19 and are categorised as “reliant” if they are above the 75th percentile value for the share of collateral coming from real estate. Only loans to firms with existing banking relationships pre-Covid-19 are included. Data refers to collateral held against loans to non-financial corporations only.

Of course, it is entirely possible that firms which used real estate as collateral were particularly negatively affected by the Covid-19 pandemic more generally. For example, firms which owned shopping centres or office buildings that were directly affected by lockdowns may have seen a very sharp drop in revenue. It is possible that this drop in revenue may have been the main driver of their borrowing dynamics, as opposed to collateral values. Indeed, the existing empirical literature consistently flags this as a source of bias which cannot be fully addressed (e.g. Chaney et al. 2012).

However, the granularity of our dataset allows us to effectively account for this by applying the method laid out in Khwaja and Mian (2008). We focus on firms which have lending relationships with multiple banks. We then measure how borrowing outcomes for a given firm varied depending on whether or not a banking relationship had relied on real estate collateral prior to Covid. By doing this we can control for all firm characteristics which could potentially bias our results – such as the firm’s demand for loans or the revenue impact of the pandemic on that firm. We find that for a given firm, when a lending relationship had relied on real estate as collateral it received approximately one-third less credit following the outbreak of the pandemic.

Finally, we see if the revaluations which did take place had implications for firms’ capacity to borrow. Again we apply the Khwaja and Mian (2008) method, comparing outcomes for a given firm across their real estate collateralised lending relationships. We find that a firm was 21% less likely to take out a new loan following a negative revaluation. Where borrowers are highly leveraged this figure increases to 42%. The effect of revaluations on the size, interest rate and maturity of new lending is less clear, although we provide some evidence that downward revaluations were associated with smaller new loans.

Taken together our findings suggest that the collateral channel of the financial accelerator remains alive and well. Our results confirm that real estate market dynamics can play a significant role in determining credit availability. In particular, our results suggest that following the outbreak of a crisis banks may sharply reduce lending against affected types of collateral. However, we also show that existing assumptions about the role of the banking system in driving this dynamic may be overly simplistic. Most prominently, bank revaluation behaviour deviates substantially from a simple mapping of asset price dynamics onto collateral values which may be implied by a textbook understanding of the financial accelerator model.

Authors' note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and are not necessarily those held by the ECB.

References

Bernanke, B and M Gertler (1989), “Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations”, The American Economic Review 79(1): 14–31.

Chaney, T, D Sraer, and D Thesmar (2012), “The Collateral Channel: How Real Estate Shocks Affect Corporate Investment”, American Economic Review 102(6): 2381–2409.

Henricot, D, J B Eymeoud, T Garcia and A Bergeaud (2022), “Working from home and corporate real estate”, VoxEU.org, 17 Jan.

Hericourt, J, F Tripier and T Grjebine (2022), “Real estate booms are behind Europe’s productivity divergence”, VoxEU.org, 9 Sep.

Horan, A, B Jarmulska and E Ryan (2023), “Asset Prices, Collateral and Bank Lending – The Case of Covid-19 and Real Estate”, ECB working paper series No. 2823.

Khwaja, A and A Mian (2008), “Tracing the Impact of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from An Emerging Market”, American Economic Review 98(08): 1413–42.

Mittal, V, S Van Nieuwerburgh and A Gupta (2022), “Work from home and the office real estate apocalypse” VoxEU.org, 2 Nov.