The number of asylum seekers in the EU reached almost one million in 2022, the highest level since the record of 1.3 million in 2015.

In addition, nearly 4 million Ukrainians were granted protection in the EU under the Temporary Protection Directive from March 2022 to March 2023 (European Commission 2023).

The large influx of refugee migrants poses major economic and political challenges (Hatton 2016, Ruist 2016, Schonberg et al. 2016). Partly in response to such challenges, many countries have implemented policies to encourage refugee migrants to participate in the labour market and learn the local language (Frattini et al. 2018, Dustmann et al. 2022, Rapoport 2023). For example, some countries make permanent residency conditional on passing language tests. This was introduced in Denmark in 2002, in Germany in 2005, in the Netherlands in 2010, and in Norway in 2013 (Arendt 2018), and has recently been adopted in Austria, Poland, and the Czech Republic (OECD 2018).

Refugee integration policy in Denmark

In our recent paper (Arendt et al. 2023), we show that a refugee integration policy in Denmark that links permanent residency to requirements of sustained labour force participation and passing of a tougher language test led to a decrease in the labour market engagement of refugee immigrants, driven by individuals least prepared to meet the requirements. In contrast, we find evidence of improved language skills for some high ability individuals. Our study highlights that integration policies aimed at incentivising the integration of refugee immigrants may backfire if they set the bar too high without ensuring measures to support those who are less able.

Our analysis takes advantage of a 2007 reform in Denmark, which introduced two requirements for refugees to qualify for permanent residency after seven years in the country. First, the reform required the accumulation of at least 2.5 years of full-time equivalent employment. The second requirement of the reform was to pass a Danish language test at the intermediate level, a significant increase in difficulty from the introductory level (the pre-reform requirement). The reform came into force on 1 May 2007 and applied to refugee immigrants who had not completed the mandatory three-year integration program by 26 November 2006 (the date of the reform proposal).

To estimate the reform effects, we compare the labour market trajectories of refugee immigrants who were granted temporary residency between January and October 2003 (control group) with those who were granted temporary residency in between January and October 2004 (treatment group). Our empirical strategy exploits the fact that the later admitted (i.e. treated) cohorts are subjected to the new and more stringent eligibility criteria for permanent residency beginning in their third year since temporary residency but not before, whereas the earlier admitted (i.e. control) cohorts continue to subjected to the old criteria throughout.

Refugees subject to more stringent residency requirements had poorer labour market participation

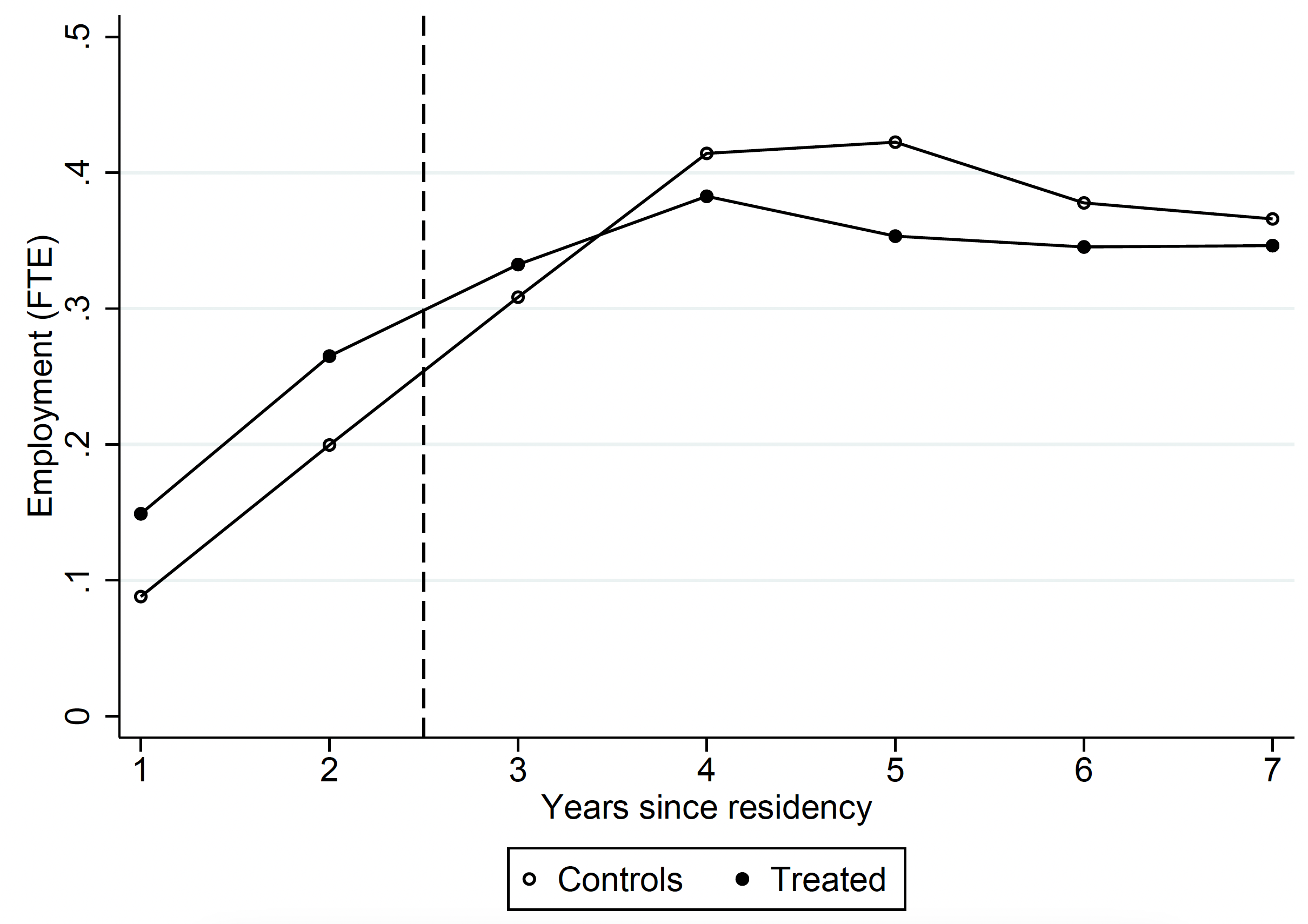

Figure 1 plots the annual employment of the treatment and control groups at each year since temporary residency (YSR). It shows that while the trends are largely similar initially, beginning in YSR of 3 (when the 2007 reform comes into effect for the treatment group), the performance of the treatment group becomes weaker relative to that of the control group. Evaluated at the mean, the estimated effect implies a decline in employment of 30%. In addition, we find no significant reform effect on the overall language test performance. This is in contrast to the reform’s intended objectives to provide incentives for refugee immigrants to better integrate into the labour market and invest in skills.

Figure 1 Employment trends for refugees in the treatment and control groups

Notes: This figure shows the trends in annual employment (in full-time equivalents) by years since temporary residency. Treated cohorts receive temporary residency in Jan-Oct 2004 while Control cohorts receive temporary residency in Jan-Oct 2003. The dashed vertical line indicates the point of reform introduction.

Disaggregating by performance level

Next, we ask whether the overall effect we find is the same for low and high performers. Until the third year after obtaining a temporary residency permit, the reform affects neither the treatment nor the control cohorts. Therefore, we use their pre-reform labour market performance to classify individuals into ‘high performers’ versus ‘low performers’, according to the amount of work experience (or language proficiency) they have accumulated up to that point. Our results are striking. We find that the negative overall employment effect shown above is largely driven by the response of low performers who reduce their labour supply in response to the reform. In contrast, we find evidence of some high performers (in particular those with high pre-reform employment performance) improving in their language skills.

Policy implications

Overall, our findings highlight that integration policies aimed at incentivising skill acquisition of refugee immigrants by setting a higher standard (e.g. for obtaining permanent residency) will only be effective if the bar is set at an appropriate level. If the requirements are seen as too costly for some, such policies may be ineffective or even create disincentive effects, leading to outcomes that are inferior to those in the absence of the policy. This is a particular concern for those who are poorly prepared for the labour market in the host country. One possible response is to combine policies that set higher incentive targets with appropriate measures to support low performers.

References

Arendt, J N (2018), “Integration and permanent residence policies – a comparative pilot study,” The ROCKWOOL Foundation, Study Paper no. 130.

Arendt, J N, C Dustmann and H Ku (2023), “Permanent residency and refugee immigrants’ skill investment”, Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming.

Dustmann, C, H Ku and J N Arendt (2022), “Refugee migration and the labour market: Lessons from 40 years of post-arrival policies in Denmark”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Hatton, T (2016), “The migration crisis and refugee policy in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 23 May.

Frattini, T, L Minale and F Fasani (2018), “(The struggle for) refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe”, VoxEU.org, 9 April.

European Commission (2023), “Temporary protection for those fleeing Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine: one year on”, 8.3.2023 COM(2023) 140 final.

OECD (2018), International Migration Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing.

Rapoport, H (2023), “Labour market access for Ukrainian refugees”, VoxEU.org, 9 January.

Ruist, J (2016), “Fiscal cost of refugees in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 28 January.

Schonberg, U, L Minale, F Fasani, T Frattini and C Dustmann (2016) “On the economics and politics of refugee migration”, VoxEU.org, 18 October.