A long-standing question confronting advanced economies is whether their unfunded old-age public pension systems are sustainable (e.g. Pérez-Díaz and Domenech 2013, Soto et al. 2021). Recently, this has been brought into sharp focus by the violent demonstrations in France over the increase in the pension age from 62 to 64. The issue has also been raised in the UK and the US.

In a recent paper (Heer et al. 2023), we find that these concerns are fully justified. Most of the 12 advanced countries that we study (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, the UK, and the US) are projected to require reforms in the next 10–20 years if their pension systems are to be sustainable. For some, the problem is even more urgent.

Public pensions occupy a substantial, often double-digit, share of both national income and social expenditures. The costs and benefits affect people for most of their lives. The main threats arise from ageing populations and changing working patterns, with a larger share of the population demanding state pensions but a smaller share of active workers being responsible for funding them. To add to these long-run factors are various short-run issues that affect the fiscal stance of many countries, such as weak growth, rising interest rates, and soaring government indebtedness.

Our analysis uses two new statistics. The first, the pension space, measures how much scope a government has to finance public pensions from the taxation of labour income. Pension space is an adaptation to public pensions of the widely-used notion of the fiscal space. It condenses diverse macroeconomic and demographic information related to public pensions into a single statistic.

The second, the pension space exhaustion probability, measures the probability that the pension space reaches zero at some point in the future because of demographic uncertainties. From these uncertainties, an empirical distribution of pension space exhaustion probability can be derived. This can be used both to assess the urgency of pension reforms and their effectiveness.

Pension space and pension space exhaustion probability are derived from a general equilibrium, life-cycle model featuring overlapping generations of households, a competitive production sector, and a government that finances both consumption and transfers using distortionary labour, capital, and consumption taxation, issues non-contingent debt, and runs a pay-as-you-go pension system. The model is calibrated for each of the 12 countries using data up to 2020. Pension space and pension space exhaustion probability are calculated for 2020 and projected up to 2050 using United Nations data.

The model captures the key feature that undermines the sustainability of pension systems, namely, the ability of labour taxation to raise sufficient revenue to pay for pensions. This is the result of Laffer effects. Having obtained the pension limit – the maximum available tax revenues from labour income due to Laffer effects to fund pensions – pension space is then calculated as the gap between pension limit and aggregate pension expenditures. It is measured as a proportion of the pension limit in any given period. The size of the pension space depends on the demographic structure of the population and the characteristics of the pension system such, as the retirement age and the replacement rate.

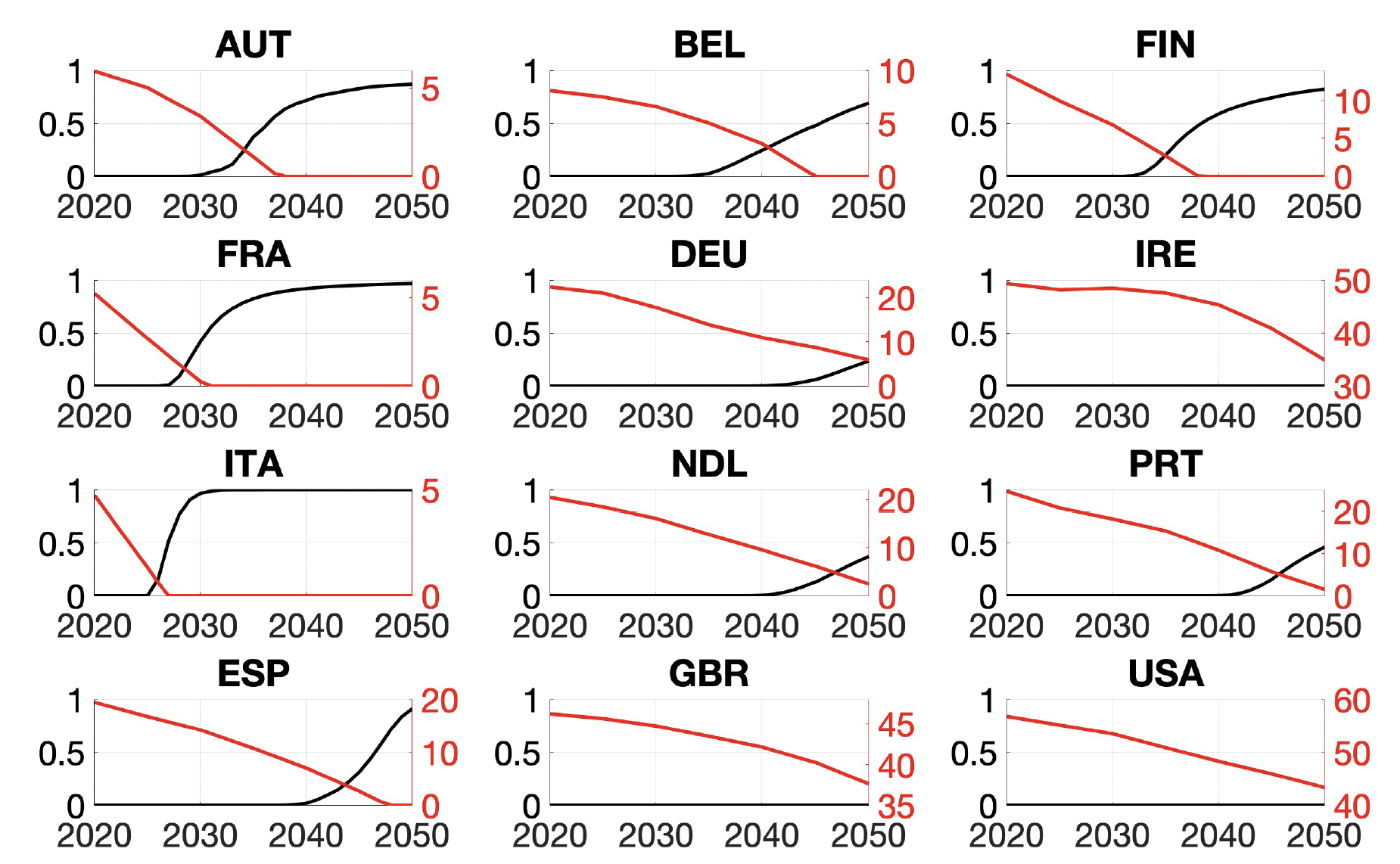

Our main findings are that pension space in 2020 varies across countries from roughly 5% to 57%. Only three countries (the US, the UK, and Ireland) have a pension space greater than 40%. This means that the expenditure on public pensions is at least 40% less than the upper limit of revenues available from labour taxation. Five countries (Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain) have a pension space between 10% and 25%. Four countries (Belgium, Austria, France, and Italy) have pension space below 10%. For France and Italy, pension space reaches zero by 2030; for Austria and Finland, it does so by 2040. The full set of results for pension space in 2020 is given in our paper, and the projected evolution of pension space until 2050 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Evolution of pension space exhaustion probability (black lines) and of pension space (red lines) during 2020–2050

Pension space is determined mainly by two factors: the replacement ratio (the generosity of the pension system) and the scope for raising labour taxes, which is smaller when the labour tax rate is larger. The three countries with the largest pension space values have the smallest replacement rates and the smallest tax rates.

The four countries with the smallest pension space values have the largest replacement rates and largest tax rates. The explanation is that if, for example, pension payments increase, then aggregate savings and hence capital fall, thereby reducing the supply of labour and hence consumption, income, and tax revenues. The labour income tax rate has to increase in order to satisfy the government budget constraint.

The evolution of pension space from 2020 to 2050 and the implications for pension space exhaustion probability are shown in Figure 1. They indicate that for the last two groups of countries, their pension space is projected to reach zero, or be very close to zero, before 2050. For France and Italy, this is projected to happen by about 2030.

It is clear from these results that pension reform will be required sooner or later. Three stylised reforms are considered:

- an increase in consumption taxation by 5%

- a reduction of the pension replacement rate by 10%

- an increase of the retirement age by two years

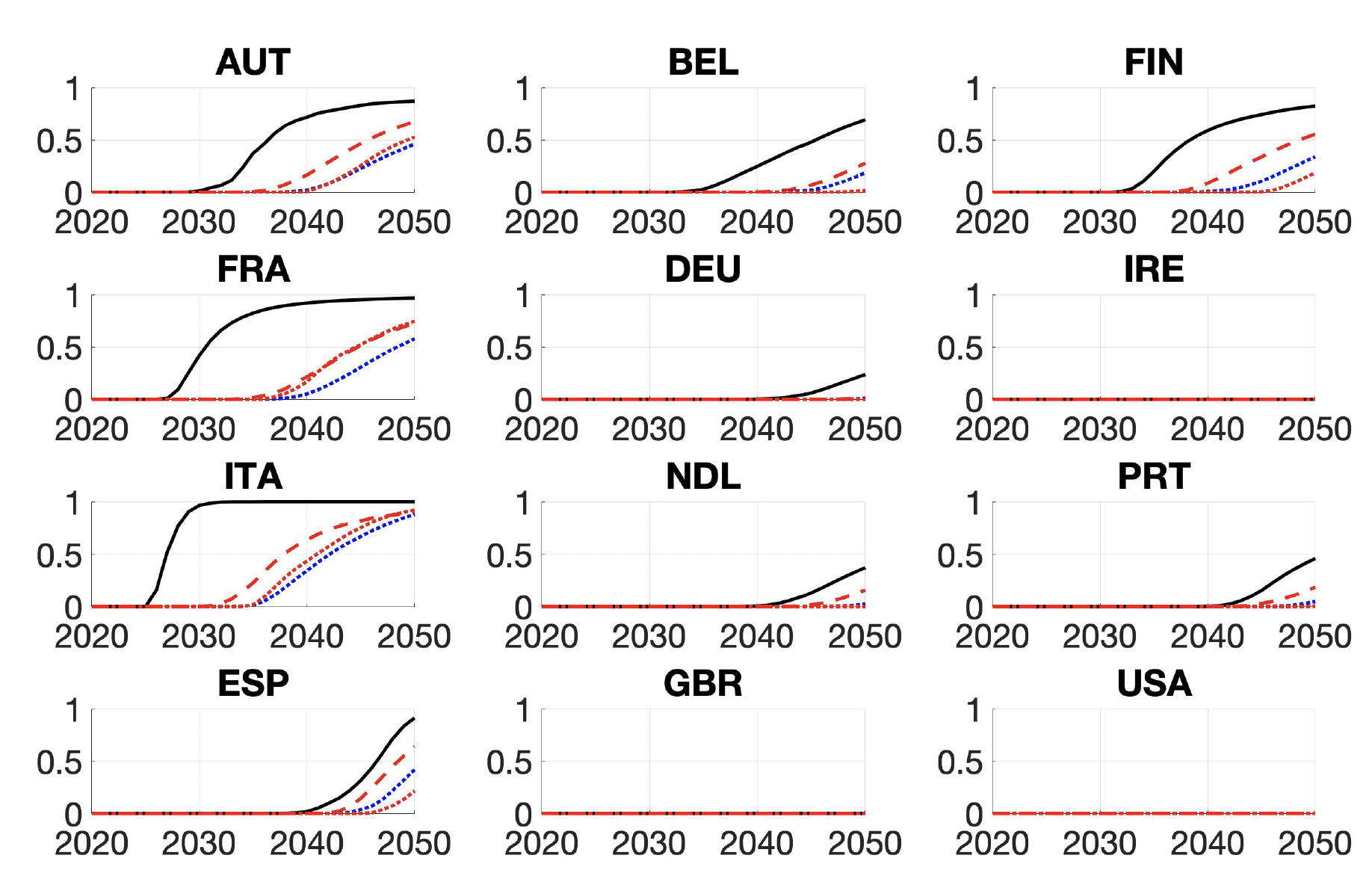

Figure 2 shows the results of these reforms. For all countries, except Ireland, the UK, and the US, the date at which the pension space is projected to be exhausted is increased by about 10 years. Larger pension reforms would extend the date further and cause pension space exhaustion probability to decrease in each country.

Figure 2 Pension space exhaustion probability with three reforms

Notes: Pension space exhaustion probability under benchmark calibration (solid black), partial financing with 5% increase of consumption tax (P1, dashed red), 10% reduction of the replacement rate (P2, dotted red), two-year increase of retirement age (P3, dotted blue), based on the empirical distribution of the population growth projections for 2020 to 2050.

These stylised reforms are not strictly comparable. One way to make them more comparable is to standardise their effect on pension space exhaustion probability in 2050 to be the same and then determine their implications for consumption, a measure of welfare.

All countries would need to decrease their replacement rates (by between roughly 3 to 14 percentage points) in order to achieve a pension space exhaustion probability similar to that obtained from increasing the age of retirement by two years in 2050. Alternatively, there would need to be an increase in consumption tax rates, ranging from roughly 6 to 10 percentage points.

Increasing indirect taxation yields welfare gains for 11 countries, ranging from 0.01% to 2.7% of consumption per capita. Italy is the only country recording a welfare loss. Reducing pension payments would produce welfare gains for ten countries, ranging from around 0.12% to 2.8% of consumption per capita.

Welfare losses, albeit marginal (0.27% and 0.24%), are found only for France and Germany. The explanation is that the welfare benefits from a given pension policy reform are higher where the associated reduction in the tax burden is greater.

For the majority of countries, increasing consumption taxation or reducing pension payments are the preferred policies, because these entail lower levels of distortionary labour income taxation compared to an increase in the retirement age.

The economic case for pension reform is clear. Whether the political will is there remains to be seen.

References

Heer, B, V Polito, and M R Wickens (2023), “Pension system (un)sustainability and fiscal constraints: A comparative analysis”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP18181.

Pérez-Díaz, V and R Domenech (2013), “The new sustainability factor of the public pension system in Spain”, VoxEU.org, 11 December.

Soto, M, A Kangur, S Romero Martinez and A Fouejieu (2021), “Rethinking pension systems in Europe for a post-Covid-19 world”, VoxEU.org, 2 October.