Trade policies often create winners and losers within a society. Lowering tariffs on apparel imports, for example, may benefit consumers by reducing prices and harm domestic clothing manufacturers by increasing competition. The literature on the political economy of trade policy offers many theories to explain why politicians may favour certain constituents in this way.

In each theory, researchers combine details about the political process with a basic model of the economy to predict trade protection. For example, in arguably the most influential of such theories, Grossman and Helpman (1994) describe how special interest groups make political contributions that lead politicians to pass trade policies in their favour. Economists Goldberg and Maggi (1999) later confirmed the Grossman-Helpman theory’s predictions using data on US trade protections in the year 1983. Similarly, Choi and Lim (2023) ask how electoral politics has impacted recent US policy on US agricultural tariffs and subsidies.

Using revealed preferences to measure welfare weights

In a recent paper (Adão et al. 2023), we propose a different approach. Rather than testing a specific theory of political economy based on its predictions for tariffs, we turn this logic on its head, using actual tariffs to directly infer who the politically favoured are. Our approach allows us not only to reveal which groups tariffs prioritise, but also to quantify the value that society implicitly places on the income of different groups in society, i.e. the groups’ welfare weights. This method is grounded in the logic of revealed preference, or the idea that one can infer a decision-maker’s preferences from their choices – though in this case the ‘decision-maker’ whose behaviour is under study is society and its policy choices.

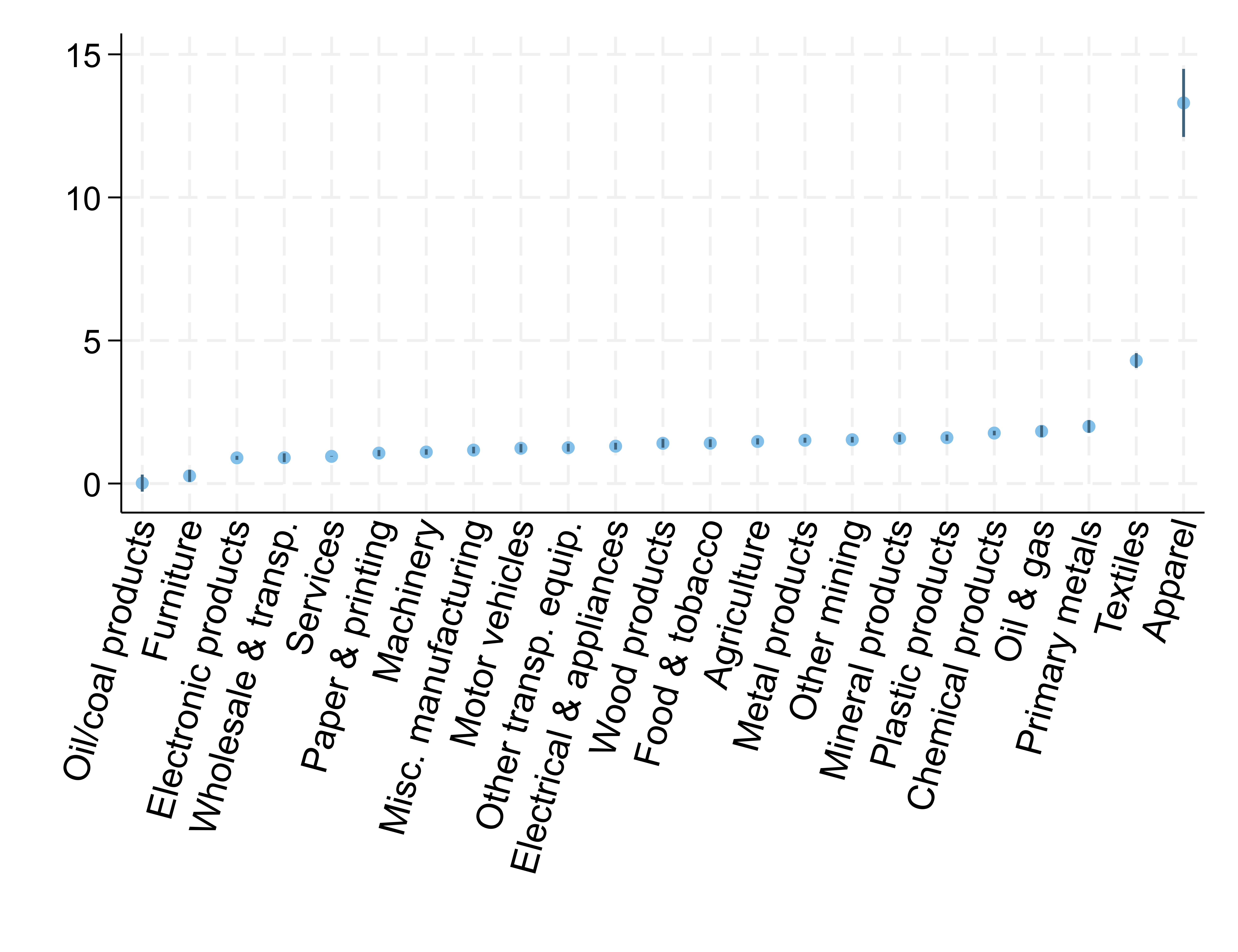

We apply this method to US trade policy in 2017. We combine information about which goods face higher tariffs as well as how tariffs impact the earnings received by different individuals. We find that politicians indeed ‘pick favourites’ – $1 received by an individual at the 99th percentile of our estimates of welfare weights is valued equally to $1.91 received by an individual at the 10th percentile. This variation is mostly driven by large differences in welfare weights between people who work in different industries. Tariff policy implies that society values income received by those who work in the apparel, textiles, and metals industries 450% more than income received by the average US individual.

Figure 1 Welfare weights by industry

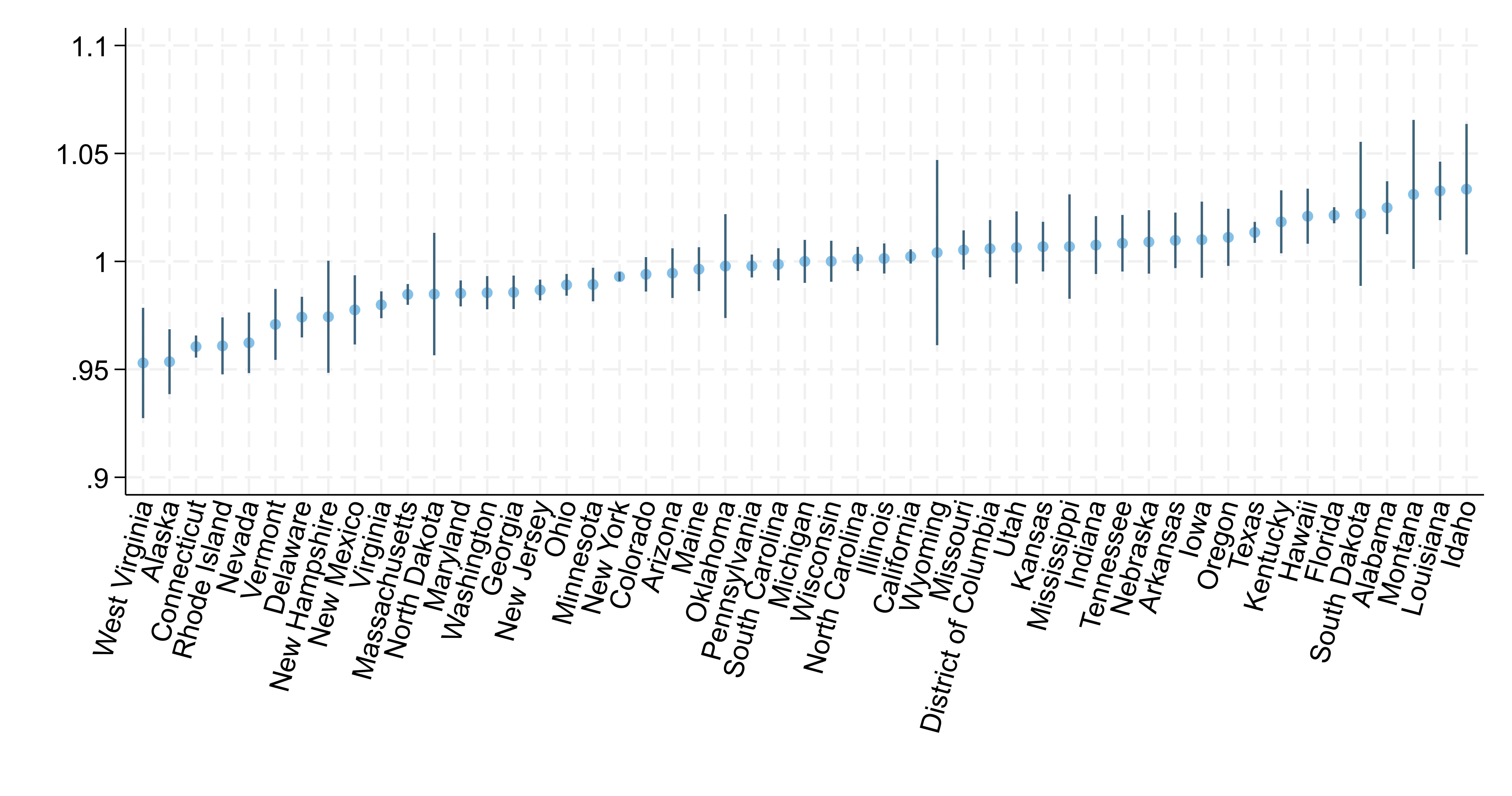

By contrast, 2017 trade policies treat states more equally. Society values income received by residents of Idaho, the state with the highest welfare weight, only 8% more than that received by residents of West Virginia, the state with the lowest welfare weight.

Figure 2 Welfare weights by US state

How important is redistributive trade protection?

Our approach allows us to evaluate the overall importance of redistributive trade protection, both in terms of shaping the variation in tariffs across different goods and in terms of generating income transfers across individuals.

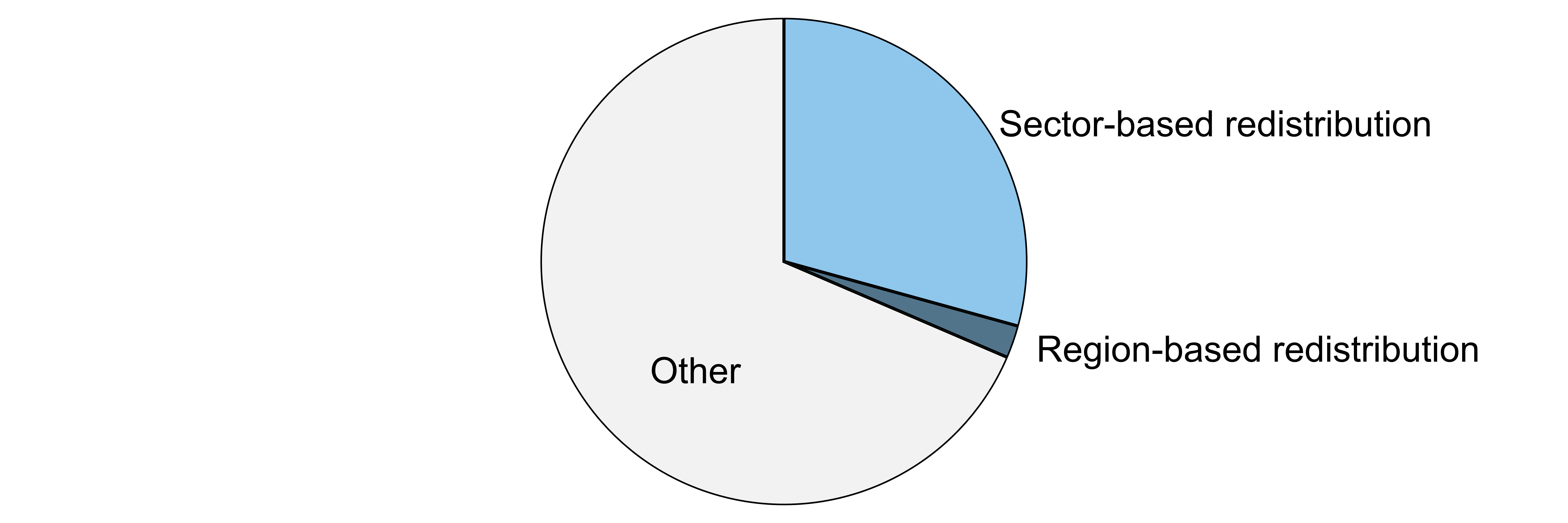

We find that redistributive motives, either due to sector- or region-based considerations, account for about one-third of the total variation in US import tariffs in 2017. Sector-based motives for redistribution explain the lion’s share of total redistributive motives (27.2%), implying that region-based considerations are relatively minor, at 2.0% of the total variation in import tariffs.

Figure 3 Redistributive motives

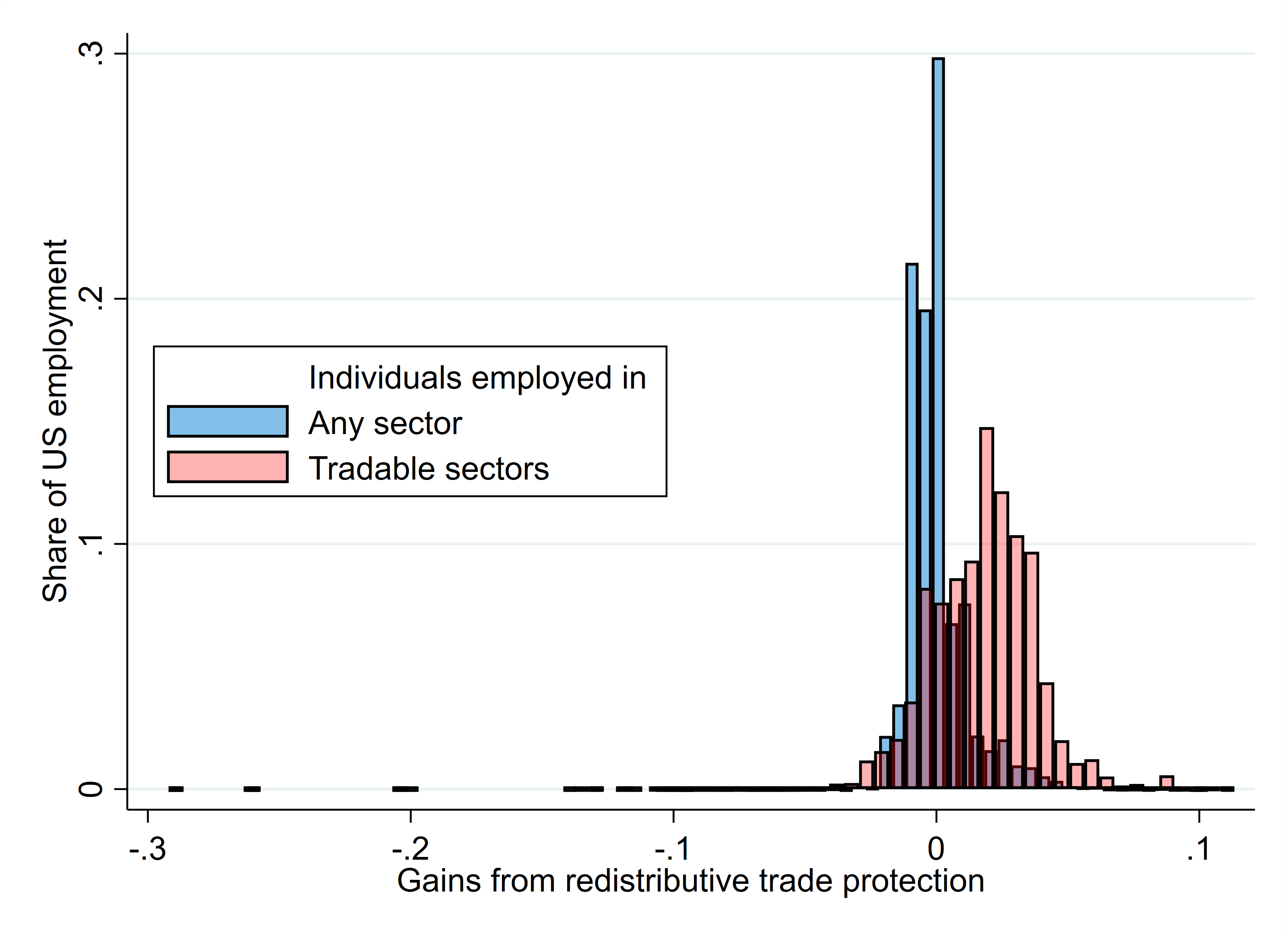

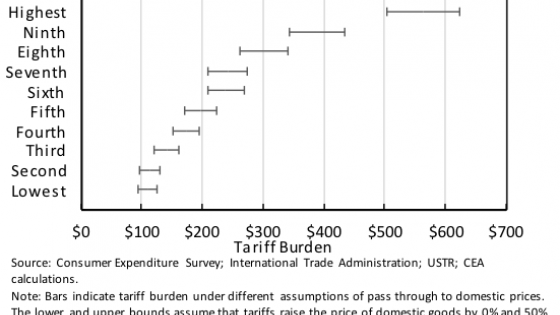

Another way to evaluate the importance of redistributive protection is to ask, from an economic rather than a statistical standpoint: how large are the monetary transfers caused by redistributive trade protection? We find that these transfers are large. Transitioning to a hypothetical US economy where everyone is valued equally would shift roughly $2,400 per worker each year from region-sector pairs at the top decile of our welfare weights to those at the bottom decile. Not surprisingly, these gains tend to be concentrated among workers employed in tradable sectors.

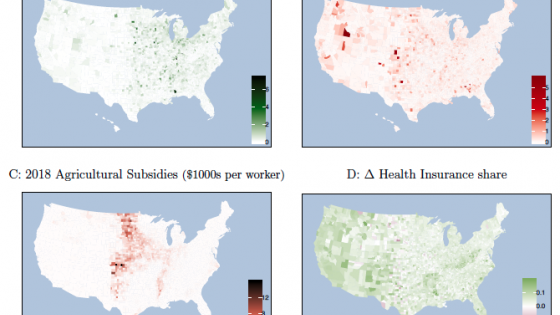

Figure 4 Gains from redistributive trade protection

Winners and losers from redistributive trade protection

The previous results show that trade policy is associated with substantial income transfers to workers in certain industries. We conclude by assessing the role of two leading explanations from the political-economy literature: sectors’ ability to lobby and states’ ability to swing presidential elections.

The sectors that lobby most intensively are clear winners from redistributive trade protection. Industries such as apparel, chemicals, electronics, appliances, food, machinery, and wood receive almost $5,000 per worker annually through tariff protections, despite spending less than $100 per worker annually on lobbying. Put differently, society implicitly values transfers toward workers employed in high trade-lobbying sectors 68% more than transfers to average US workers.

By contrast, swing states (Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Ohio, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin) do not appear to garner special treatment from politicians, at least in terms of tariff protection observed in 2017.

Standard approaches to the political economy of trade explain how specific features of the political process shape trade policy. We reverse this approach, using trade policy to explain who the politically favoured are and the size of the income transfers they receive. We hope that this research offers a blueprint for identifying these groups in other contexts; environmental policy, competition policy, and financial regulation are all areas to which this would be straightforward to apply.

References

Adão, R, A Costinot, D Donaldson, and J Sturm (2023), “Why is trade not free? A revealed preference approach”, BFI Working Paper Series 136.

Choi, J and S Lim (2023), “The political economy of trade protection: Evidence from the 2020 US presidential election”, VoxEU.org, 15 September.

Grossman, G M, and E Helpman (1994), “Protection for sale”, American Economic Review 84(4): 833–50.

Goldberg, P, and G Maggi (1999), “Protection for sale: An empirical investigation”, American Economic Review 89(5): 1135–55.