Matching frictions in the labour market are central for understanding the roots of high unemployment and labour shortages in modern economies. Next to the adverse effects on aggregate economic activity, matching frictions impede efficient job-worker allocations with detrimental consequences for firm productivity and workers’ wage growth (e.g. Guvenen et al. 2020, Kugler et al. 2021, Tåg et al. 2022).

In order to deal with costly and time-intensive job search and recruiting activities, workers and firms apply various strategies. In particular, both sides of the labour market make use of different search channels to reduce search costs and facilitate better match quality. While job postings allow firms to reach many suitable applicants, networks of personal contacts help workers and firms gain information about each other prior to job interviews (e.g. Brown et al. 2016, Cappellari and Tatsiramos 2015, Dustmann et al. 2016). Further, in many European countries, public employment agencies help job seekers through bespoke job search assistance (Lalive et al. 2018, Belot et al. 2019, Merkl and Sauerbier 2023).

While previous research has studied the effects of specific search channels on workers’ labour market outcomes, little is known about the overall use of search channels by workers and firms and the resulting match outcomes. Understanding the extent to which search channels have differential effects on the matching process is key for the analysis of wage inequality, aggregate productivity, and other labour market outcomes.

In a recent paper (Carrillo-Tudela et al. 2023), we make use of unique linked data to investigate the degree to which search channels affect the matching process between heterogeneous firms and heterogeneous workers. These data – provided by Germany’s Institute for Employment Research (IAB) – combine a worker survey about job search behaviour, a firm survey about recruitment behaviour, and an administrative firm-worker dataset containing the full employment and earnings biographies of private-sector employees in the German labour market. The two survey datasets not only provide information about firms’ and workers’ use of search channels, but also about the search channel that led to a hire (of a firm) or to a new job (of a searching worker). These data reveal that job postings and personal networks are the two dominant search channels in the German labour market, accounting together for almost 70% of all hires (followed by the public employment agency, which accounts for another 13% of hires).

The administrative matched worker-firm dataset can be used to estimate wage ranks of firms and workers based on AKM fixed effects (so-named for the authors of Abowd et al. 1999; see also Card et al. 2013). Broadly speaking, a firm with a high AKM fixed effect pays higher wages relative to a firm with a lower AKM fixed effect irrespective of the workforce quality, possibly because the former firm is more productive. Likewise, a worker with a high AKM fixed effect tends to earn a higher wage at any firm relative to another worker with a lower AKM fixed effect, possibly because the former worker has better skills.

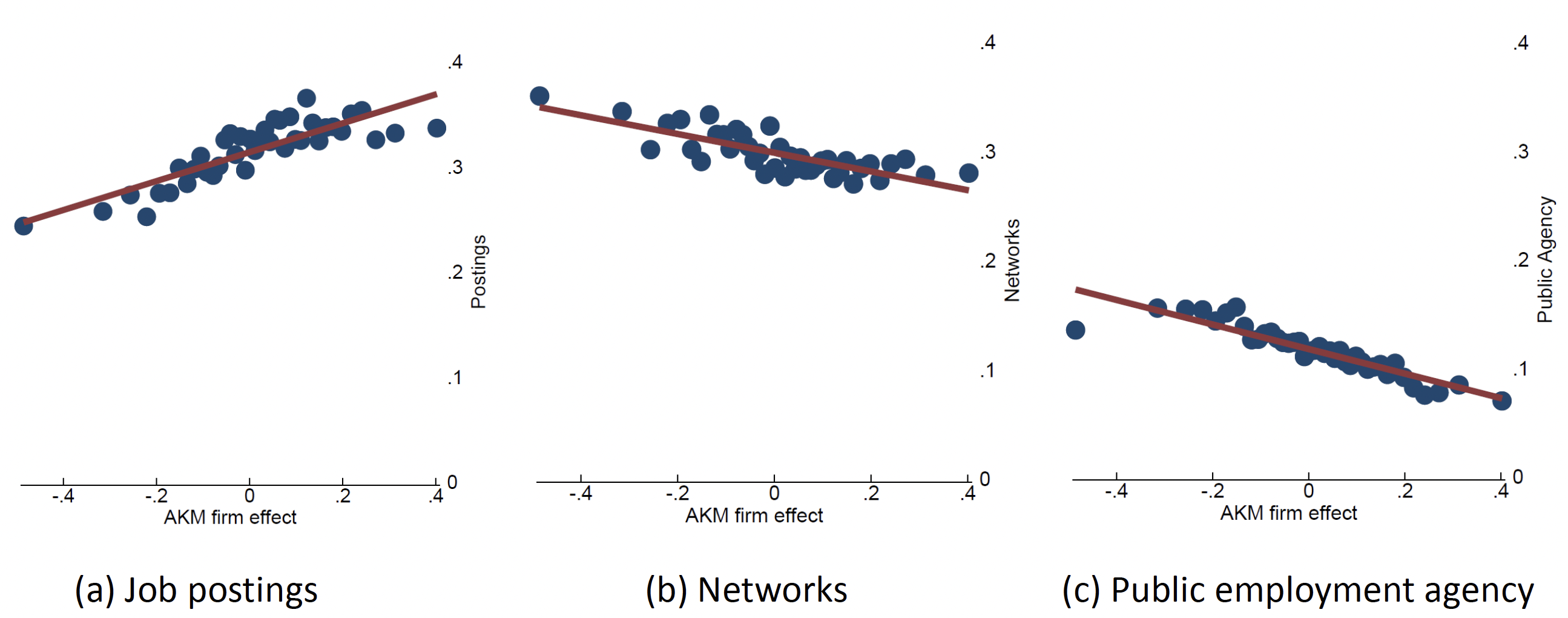

Linking these AKM fixed effects to the two survey datasets allows us to examine how firms and workers of different wage ranks match in the labour market. Figure 1 shows the relationships between the firms’ AKM fixed effects and the probability of hiring through either job postings, networks, or the public employment agency. As can be seen, high-wage firms hire more frequently via job postings compared to low-wage firms, while they succeed less often through networks or through the public employment agency where low-wage firms are more likely to hire. Importantly, these relationships are conditional on the educational requirement of the job and on firm size, firm age, or industry, which all matter independently for recruitment strategies. These results show that firms of different wage ranks match differentially through the three search channels, regardless of other important firm or job characteristics.

Figure 1 Hiring probability through job postings, networks, and public employment agency by firms’ wage ranks

Source: Carrillo-Tudela et al. (2023)

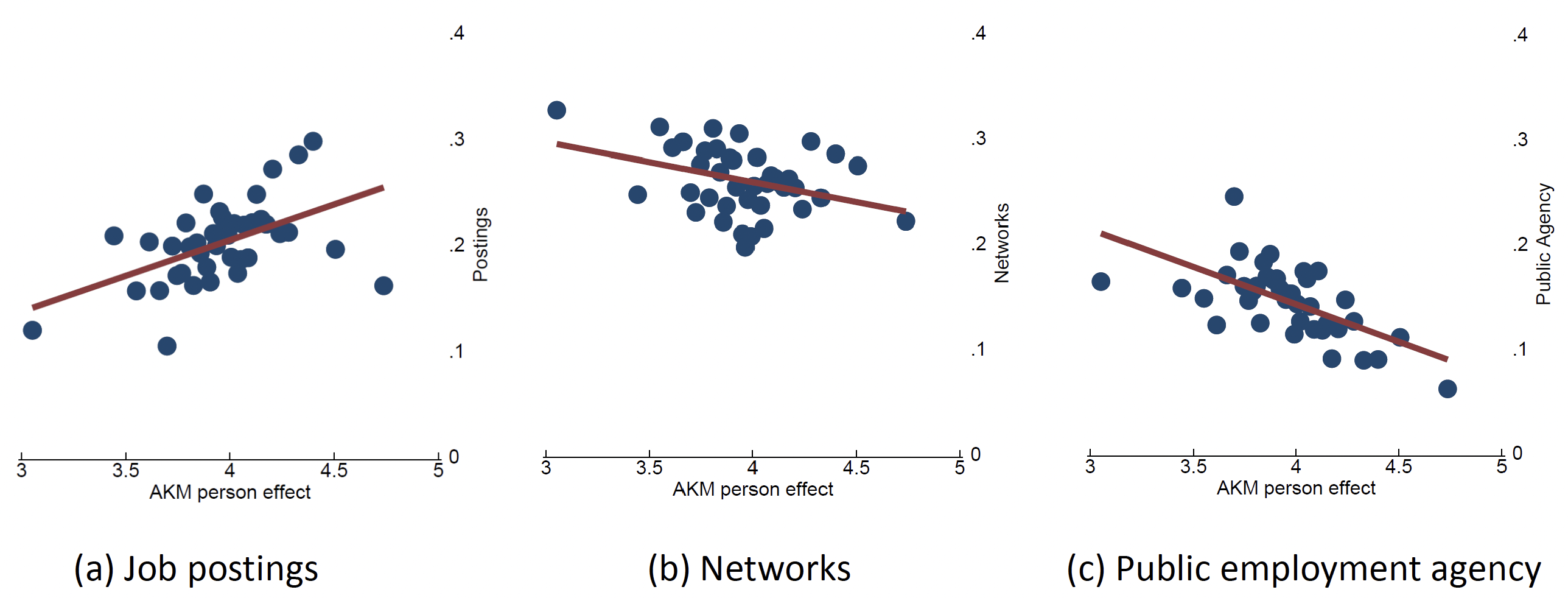

Figure 2 illustrates the corresponding relationships between the workers’ AKM fixed effect and the probability of finding a job through job postings, networks, or the public employment agency. The results are strikingly similar to those on the firm side: high-wage workers are more likely to find a job via postings compared to low-wage workers, while low-wage workers are more likely to find a job via networks or the public employment agency compared to high-wage workers. These relationships are conditional on various worker characteristics such as age, gender, and previous employment status, as well as the occupation of the job. Hence, the relationships between the worker’s wage rank and the successful search channel are not driven by composition effects along these dimensions.

Figure 2 Probability of finding a job through job postings, networks, and public employment agency by workers’ wage ranks

Source: Carrillo-Tudela et al. (2023)

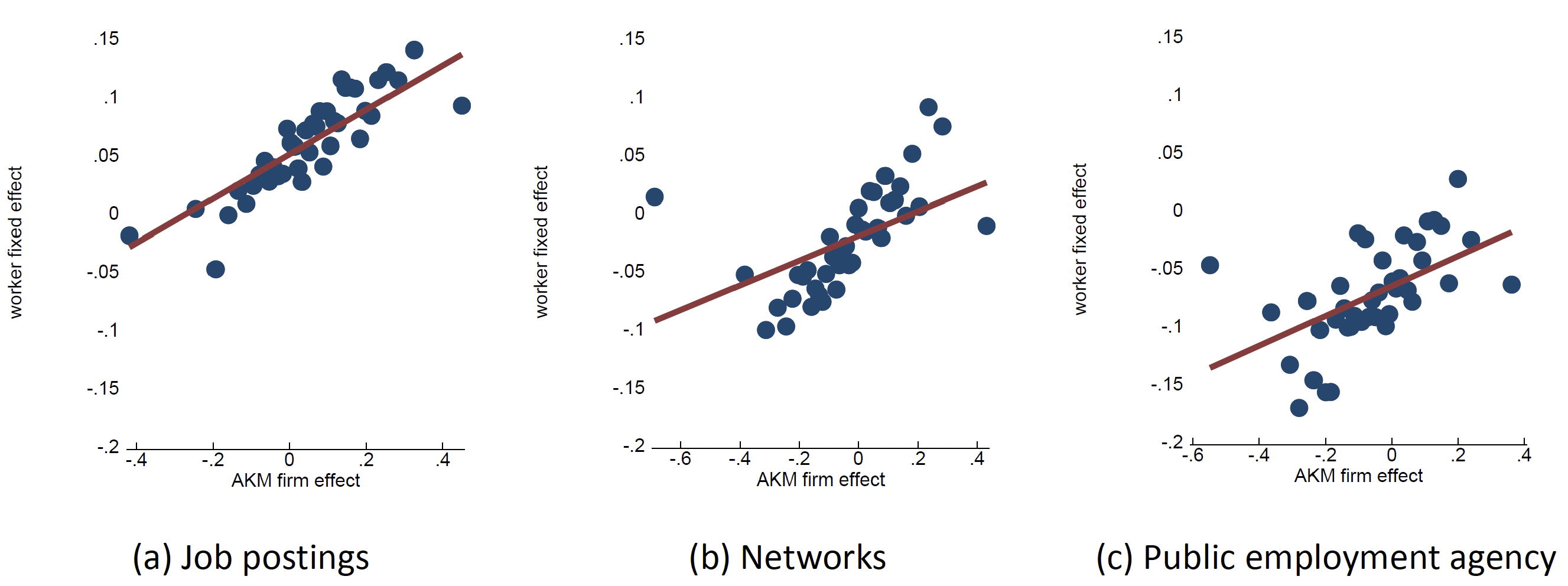

Taken together, our results indicate that high-wage firms and high-wage workers match more frequently via job postings, while low-wage firms and low-wage workers match relatively more via networks or the public employment agency. To investigate the role of search channels for labour market sorting, we go a step further. Separately for each of the three successful search channels – and again conditional on the firm and job controls applied previously – we consider the relationship between the hired worker’s wage rank and the hiring firm’s wage rank. The results, shown in Figure 3, lead to two conclusions. First, firms generally succeed in employing higher-ranked workers via job postings compared to personal networks and especially in comparison to the public employment agency, which generates matches with lower-ranked workers. Second, all channels facilitate positive sorting in that high-wage workers are more likely to match with high-wage workers compared to low-wage firms, where the positive sorting relationship is strongest for the job-postings channel.

Figure 3 Relationship between worker and firm wage ranks separately for the hiring channel job postings, networks, and public employment agency

Source: Carrillo-Tudela et al. (2023)

It is well understood that workers’ job mobility plays a key role for individual wage dynamics, wage inequality, and for the wage and hiring policies of heterogeneous firms (e.g. Burdett and Mortensen 1998, Postel-Vinay and Robin 2002). Our data give unique insights into the role of search channels for job-to-job turnover and wage-ladder dynamics. On the firm side, we find that job postings provide the highest probability of poaching a worker from another firm, especially for firms higher up the wage distribution. We also show that workers achieve the largest positive steps on the wage ladder when they find a job via job postings: a job-to-job transition through job postings is associated with an increase of the employer’s average wage level that is 2–3 percentage points larger compared to a job-to-job transition through the other search channels.

Given these empirical relationships, we build and estimate a structural equilibrium model with two-sided heterogeneity in order to analyse the role of search channels for productivity, wages, and employment. One important purpose of the model is to evaluate the impact of the public employment agency for aggregate and distributional labour market outcomes. As in many other countries, Germany’s public employment agency supports job seekers individually through bespoke advice from placement officers. We consider a counterfactual scenario in which this placement service is abolished, while firms and workers are allowed to redirect their search effort to the other search channels. We find that the removal of the public placement service has large macroeconomic effects: aggregate employment and output decline by 1.4% and 0.8%, respectively, where the largest employment losses are realised for workers at the bottom of the productivity distribution. Moreover, when workers at the bottom and middle of the productivity distribution find jobs, they end up employed in firms with lower average productivity. As a result, wage inequality widens such that the 90–50 and 50–10 percentile ratios go up by 3.3% and 1.2%, respectively.

Overall, our results highlight that matching technologies matter decisively for labour market outcomes: different search channels bring together workers and firms at different rungs of the wage distribution. Hence, they matter not only for individual job search outcomes, but also for aggregate employment, productivity, and wage inequality.

References

Abowd, J M, F Kramarz and D N Margolis (1999), “High Wage Workers and High Wage Firms“, Econometrica 67(2): 251–333.

Belot, M, P Kircher and P Muller (2019), “Providing Advice to Jobseekers at Low Cost: An Experimental Study on Online Advice”, Review of Economic Studies 86(4): 1411–47.

Brown, M, E Setren and G Topa (2016), “Do Informal Referrals Lead to Better Matches? Evidence from a Firm’s Employee Referral System”, Journal of Labor Economics 34(1): 161–209.

Burdett, K and D T Mortensen (1998), “Wage Differentials, Employer Size, and Unemployment”, International Economic Review 39(2): 257–73.

Cappellari, L and K Tatsiramos (2015), “With a Little Help from my Friends? Quality of Social Networks, Job Finding and Job Match Quality”, European Economic Review 78: 55–75.

Card, D, J Heining and P Kline (2013), “Workplace Heterogeneity and the Rise of West German Wage Inequality”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(3): 967–1015.

Carrillo-Tudela, C, L Kaas and B Lochner (2023), “Matching Through Search Channels”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18575.

Dustmann, C, A Glitz, U Schönberg and H Brücker (2016), “Referral-Based Job Search Nnetworks”, Review of Economic Studies 83(2): 514–46.

Guvenen, F, B Kuruscu, S Tanaka and D Wiczer (2020), “Multidimensional Skill Mismatch”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 12(1): 210–44.

Kugler, A D, U Muratori and A Farooq (2021), “The Impacts of Unemployment Benefits on Job Match Quality and Labour Market Functioning,” VoxEU.org, 7 February.

Lalive, R, Y Flueckiger, P Kempeneers and L Cottier (2018), “Job Search Assistance does not Boost Employment: New Evidence,” VoxEU.org, 27 October.

Merkl, T Sauerbier (2023), “The Reorganisation of the Federal Employment Agency Mattered for the German Labour Market Upswing, but in an Unexpected Way,” VoxEU.org, 25 April.

Postel–Vinay, F and J M Robin (2002), “Equilibrium Wage Dispersion with Worker and Employer Heterogeneity”, Econometrica 70(6): 2295–350.

Tåg, J, M Pagano, A Scognamiglio and L Coraggio (2022), “The Matching Between Workers and Jobs Explains Productivity Differentials Across Firms,” VoxEU.org, 9 May.