A fundamental issue in economics is how firms pass cost shocks (taxes, exchange rates, input prices) through to prices. In 1890, Alfred Marshall, in his Principles of Economics, wrote that “there is scarcely any economic principle which cannot be aptly illustrated by a discussion of the shifting of the effects of some tax ‘forwards,’ i.e. towards the ultimate consumer…”. Indeed, since then, the study of how firms pass cost shocks through to prices touches almost any field in economics, including taxation in public economics, exchange rates (Bonadio et al. 2016) and tariffs in international trade, input prices and merger analysis in industrial organisation (Ashenfelter et al. 2013), and financial (Agarwal et al. 2016) and monetary policy transmission in macroeconomics (Carrière-Swallow et al. 2017). However, although theoretical analysis shows that competition is a key determinant of pass-through (Weyl and Fabinger 2013, Miklós-Thal and Shaffer 2021, Adachi and Fabinger 2022), empirical evidence on this issue is scant. The main challenge is distinguishing local markets while accounting for the endogeneity of market structure.

Pass-through and competition

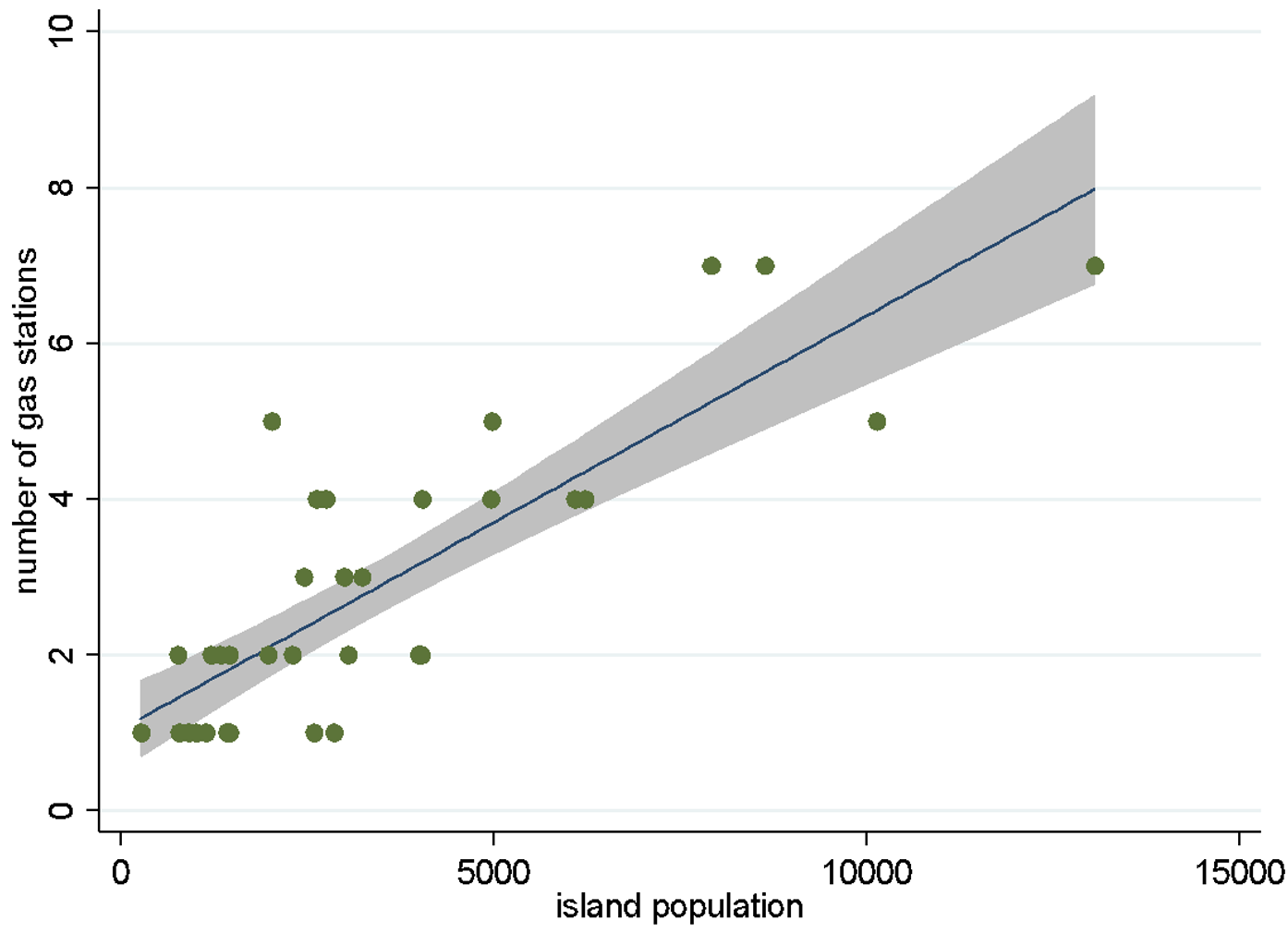

In this line of research, we examine the retail market for petroleum products and strategically choose to focus on the many small islands Greece is known for. Some of these islands are so small that they have just a single gas station, while others have two, three, or more. The naturally occurring variability in island size provides an exogenous source of variability in the level of competition (Figure 1). Islands clearly define local markets, as substitution effects between islands are zero.

Figure 1 Competition and market size in Greek islands

Notes: Figure 1 plots the relationship between the population on each island and the number of gas stations.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Greek Ministry of Development and Competitiveness and the Hellenic Statistical Authority.

Along with this unique setting, we take advantage of a number of significant policy changes. At the beginning of the financial crisis in 2010, the Greek government increased the excise duty on petroleum products three times. The increments were large and unannounced and provided us with an ideal exogenous shock for estimating the pass-through to retail prices. For political reasons, heating diesel was excluded from the excise hikes, as it was considered a necessity good.

Using daily gas station data, we study how the pass-through of the excise duty tax varied across markets with different numbers of competitors, while using heating diesel as a control group. Thus, we can account for unobserved heterogeneity across islands and gas stations, and control for the daily aggregate price fluctuations of petroleum products using the control group.

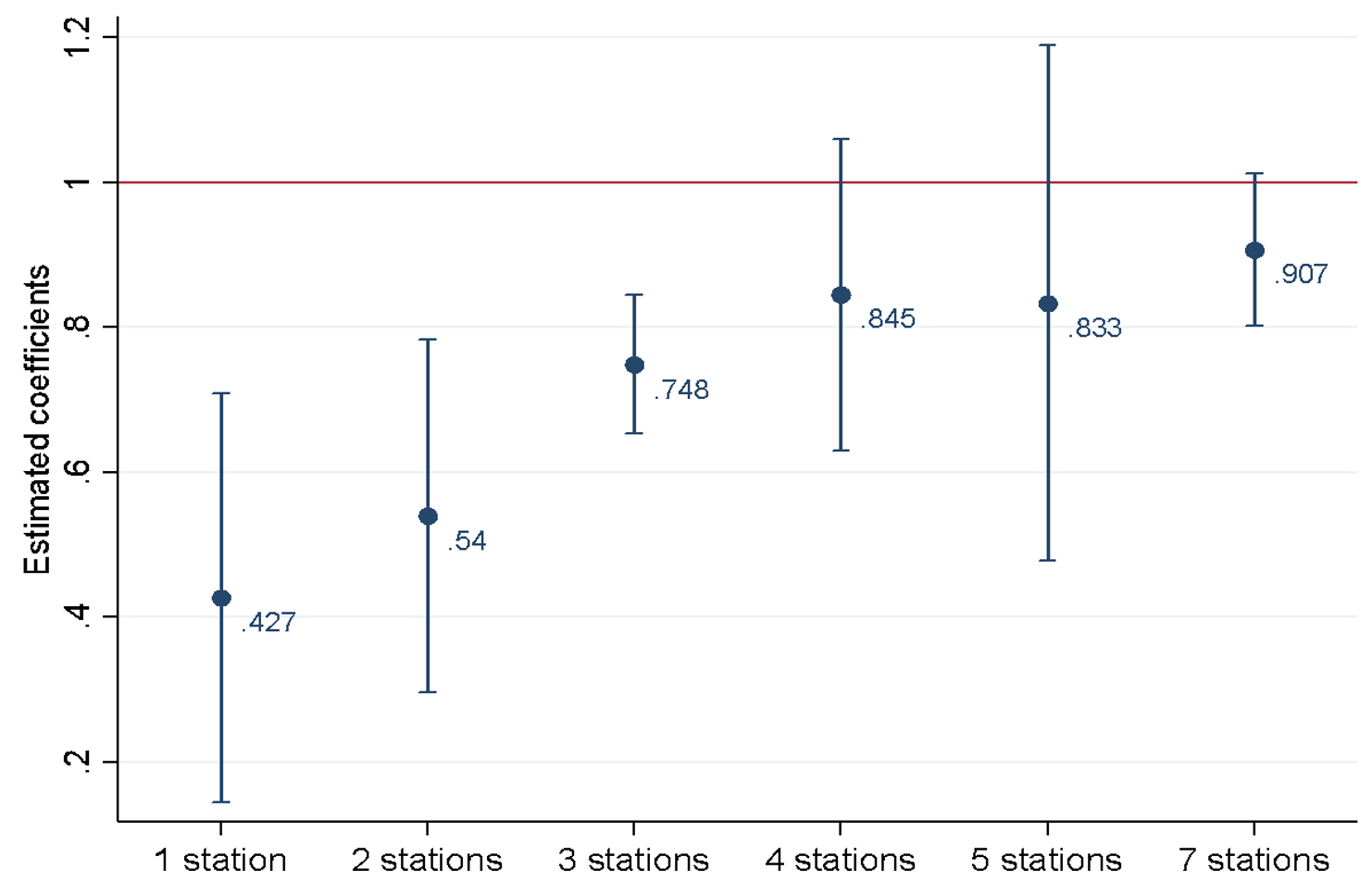

As shown in Figure 2, we find that pass-through increases significantly with the number of competitors, and the relation between competition and pass-through is nonlinear. On average, the pass-through is 0.43 on monopolistic islands and grows to about 1 on islands with four or more competitors. Hence, perhaps counter-intuitively for a non-economist, the more market power firms have, the less they are going to pass through increases in costs. This is important not just for fiscal policy but also for antitrust authorities, for example, when they examine the pass-through of cartel pricing or other abuses along the supply chain.

Figure 2 Pass-through and competition

Notes: Figure 2 plots the estimated coefficients together with the 95% confidence interval of the semi-parametric relationship between the number of competing gas stations and tax increases pass-through. For more information, see Genakos and Pagliero (2022).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Greek Ministry of Development and Competitiveness.

We also find that competition affects the speed of adjustment. This is an important issue, as it relates to understanding how quickly prices adjust to cost shocks in the economy. We find that price adjustments are larger and occur more quickly in more competitive markets, leading to faster pass-through in more competitive markets. This is critical for governments to know since it relates to how quickly they should expect to see results on consumer prices, as well as an implicit indicator of how competitive markets are.

Asymmetric pass-through and competition

Is the response to tax increases the same as it is to tax cuts? Over the past thirty years, a large literature shows that retail prices respond faster to marginal cost increases than to decreases (Benzarti et al. 2020). This asymmetric pass-through, or asymmetric price adjustment, also known as the ‘rockets and feathers’ phenomenon, was first studied by Bacon (1991) in relation to several enquiries by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in the UK gasoline market.

Although market power was the first conjectured explanation for the asymmetric response, surprisingly few empirical papers provide specific evidence on the relationship between competition and asymmetric pass-through. The main reason is that it is hard to simultaneously identify the asymmetry of price responses and the relationship between asymmetry and competition.

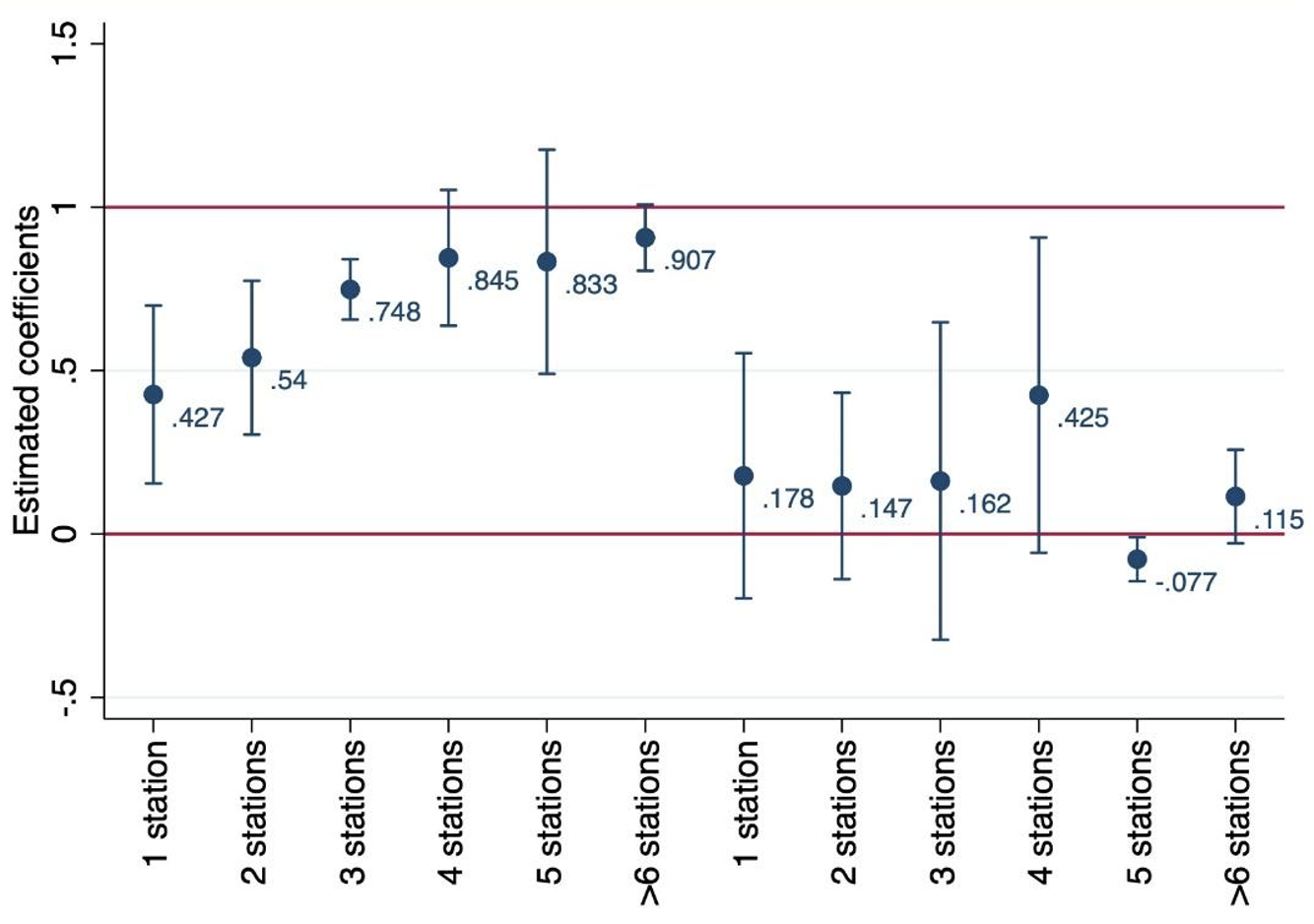

Using the same Greek islands, we study the relationship between competition and pass-through by examining a 20% reduction in the excise duty for diesel only, which was implemented in October 2012, while using unleaded 95 petrol as our control group. In Figure 3, we compare the pass-through for the tax increases and the tax decrease. We find that, on average, the pass-through of the tax hikes (average pass-through 0.7) is five times higher than for the tax decrease (average pass-through 0.14), confirming the strong asymmetry in the literature. Most surprisingly, though, we see that the pass-through of the tax hikes increases with the number of competitors, whereas that of the tax decrease does not vary with competition. Hence, we document for the first time a strong asymmetric competition effect.

Figure 3 Asymmetric pass-through and competition

Notes: Figure 3 plots the estimated coefficients together with the 95% confidence interval of the semi-parametric relationship between the number of competing gas stations and tax increases (first half) and tax cut (second half) pass-through. For more information, see Genakos, Lyu and Pagliero (2023).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Greek Ministry of Development and Competitiveness.

We also find a significant asymmetry in the speed of price adjustments to positive and negative shocks. The average pass-through for tax increases grows significantly with the adjustment period considered, going from 23% after one day to 71% after ten days. In contrast, the pass-through for the tax decrease grows very slowly, going from 1% after one day to only 14% after ten days. The differential impact of tax cuts must be examined carefully anytime when policymakers propose tax cuts in the belief that they will be passed on to lower consumer prices. This process is by no means automatic and it seems that competition does not help as much as one would expect.

VAT pass-through

Finally, we also examine the pass-through of ad valorem (e.g. value-added) taxes. Value-added taxes (VAT) are among the most widely used taxes across developed and developing countries, raising about a fifth of total tax revenues among OECD countries (OECD 2020).

We exploit a unique natural experiment in which the Greek government decided to equalise VAT rates (from 17% to 24%) of islands that are close to the borders of Greece with Turkey in January 2018. Those islands located near the borders of Greece are not fundamentally different from other nearby islands and hence the selection can be considered quasi-random. We use the retail market for petroleum products again, and calculate VAT pass-through by comparing prices for unleaded gasoline and diesel on the affected islands to similar islands where the rates remained unchanged. Next, we use the cross-island variation in market structure to study the impact of competition on pass-through.

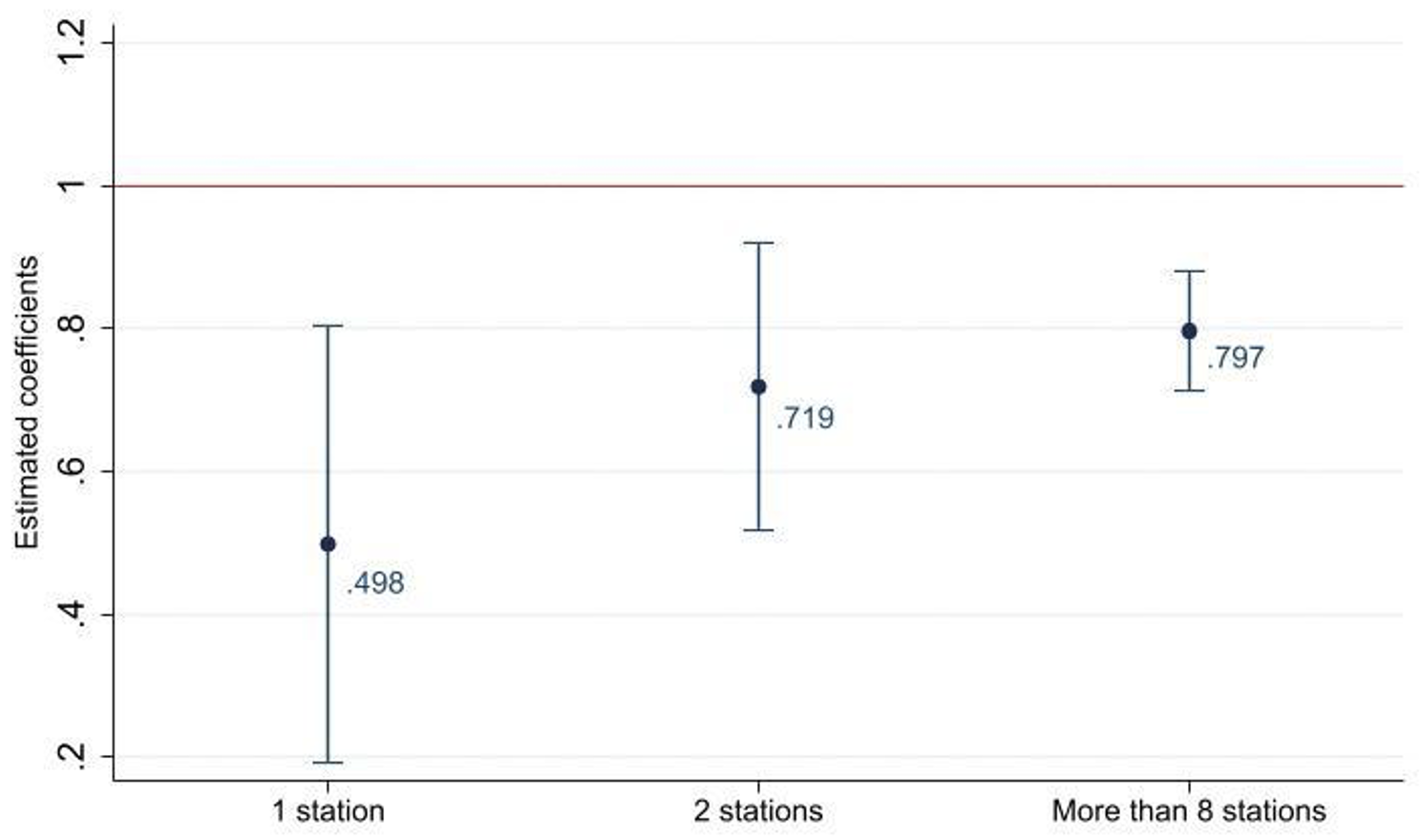

Figure 4 presents our main findings. Pass-through increases with competition, going from 0.5 in monopoly to around 0.8 in more competitive markets, but remains incomplete. This is in line with a large theoretical literature (Stern 1987, Delipalla and Keen 1992, Anderson et al. 2001, Adachi and Fabinger 2022) that emphasises that for a given degree of market power, we should expect the level of pass-through for ad valorem (percentage) taxes to be lower compared to per unit specific taxes (such as the excise duty taxes) and also recent empirical evidence from other countries (Sagimuldina et al. 2020). The intuition is that with ad valorem taxes (like VAT), the government receives a share of a firm’s gross revenue. Thus, the ability of firms to raise prices under imperfect competition also benefits the government. This reduces firms’ incentives to increase prices in comparison with the case of a specific tax, such as excise duties, which results in lower pass-through.

Figure 4 VAT pass-through and competition

Notes: Figure 4 plots the estimated coefficients together with the 95% confidence interval of the semi-parametric relationship between the number of competing gas stations and VAT tax increase pass-through. For more information, see Dimitrakopoulou, Genakos, Kampouris, and Papadokonstantaki (2023).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Greek Ministry of Development and Competitiveness.

Second, we find that the rate of adjustment for VAT changes is faster than for specific taxes and that it is faster in more competitive markets. This fast speed of convergence is a new and interesting fact in itself, as we have no theoretical guidance as to what we should expect. We conjecture that there are at least two reasons why the speed of adjustment for VAT is faster than that of excise duty. First, the VAT applies only and is paid directly by the final consumer. In contrast, the excise duty is paid at the refinery level and has to be transmitted through the whole vertical supply chain. Second, VAT changes, precisely because they apply to consumers directly, get much more publicity, and they are easier to detect in final consumer prices.

Conclusions

In this column, we summarise a line of research that provides new empirical evidence on the effects of competition on pass-through in clearly defined oligopolistic markets with a small number of firms. We contribute to the growing literature on pass-through by showing that pass-through increases with competition in a nonlinear fashion, both for specific taxes and VAT. But while the former becomes complete in a market with four firms or more, for the latter, it remains incomplete. Moreover, in both cases, the frequency of price adjustments is higher in more competitive markets. We also find that the pass-through of tax increases is five times larger than for a tax cut. Most intriguing, we show there is a very slow adjustment of prices when it comes to a tax cut and that the pass-through does not seem to vary with competition. These results have important implications for policymakers and highlight the aspects (type of tax, increase or decrease, product market competition) that need to be carefully considered before implementation.

Authors’ note: This column is dedicated to the loving memory of Mario Pagliero, a brilliant economist and dear friend who passed away too soon.

References

Adachi, T and M Fabinger (2022), “Pass-through, welfare, and incidence under imperfect competition”, Journal of Public Economics 211: 104589.

Agarwal S, S Chomsisengphet, N Mahoney and J Stroebel (2016), “Bank pass-through of credit expansions and household borrowing”, VoxEU.org, 9 Jan.

Anderson, S P, A De Palma and B Kreider (2001), “Tax incidence in differentiated product oligopoly”, Journal of Public Economics 81(2): 173-192.

Ashenfelter, O, D Hosken and M Weinberg (2013), “Did US beer mergers cause a price increase?", VoxEU.org, 18 Sep.

Bacon, R W (1991), “Rockets and feathers: the asymmetric speed of adjustment of UK retail gasoline prices to cost changes”, Energy economics 13(3): 211-218.

Benzarti, Y, D Carloni, J Harju and T Kosonen (2020). “What Goes Up May Not Come Down: Asymmetric Incidence of Value Added Taxes”, Journal of Political Economy 128(12): 4438-4474.

Bonadio B, A M Fischer and P Sauré (2016), “Fast exchange rate pass-through”, VoxEU.org, 21 Apr.

Carrière-Swallow Y, B Gruss, N Magud and F Valencia (2017), “Monetary policy credibility and exchange rate pass-through”, VoxEU.org, 13 Mar.

Delipalla, S and M Keen (1992), “The comparison between ad valorem and specific taxation under imperfect competition”, Journal of Public Economics 49(3): 351-367.

Dimitrakopoulou, D, C Genakos, T Kampouris and S Papadokonstantaki (2023), “VAT Pass-Through and Competition: Evidence from the Greek islands”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18179.

Genakos, C and M Pagliero (2022), “Competition and pass-through: evidence from isolated markets”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(4): 35-57.

Genakos, C, B Lyu and M Pagliero (2023), “Asymmetric Pass-Through and Competition”, in progress.

Miklos-Thal, J and G Shaffer (2021), “Pass-through as an economic tool: on exogenous competition, social incidence, and price discrimination”, Journal of Political Economy 129(1): 323-335.

Sagimuldina, A, M Schnitze and F Montag (2020), “VAT reduction as unconventional fiscal policy in Germany: Fast but heterogeneous pass-through in the fuel market”, VoxEU.org, 25 Aug.

Stern, N (1987), “The effects of taxation, price control and government contracts in oligopoly and monopolistic competition”, Journal of Public Economics 32(2): 133-158.

Weyl, E G and M Fabinger (2013), “Pass-through as an economic tool: Principles of incidence under imperfect competition”, Journal of Political Economy 121(3): 528-583.